GLBS3800

Putin’s Russia

Memory As An End & The End of Memory

Restoration, Rehabilitation & Remembrance in Russia’s Ongoing Patriotic War

“The essence of a nation is that all individuals have many things in common, and also, that they have forgotten many things”

(Renan, 1882)

Collective Russian memory is a postmodern patchwork quilt of meaning, under which the unity achieved through post-Soviet nationalism dreams of overcoming an anxious future. I’ll stitch this quilt together from three distinct perspectives.

First, how individual metanarratives of loss of identity, and restoration of post-Soviet nationalism have motivated a political reassertion of control over Russian civic identity. Second, how restorative nostalgia and collective trauma have rehabilitated malleable post-Soviet memory surrounding Russia’s role as a key protagonist during the Second World War. And third, how nostalgia as a political instrument has agitated Russian relations with the West, turning memory war into actual war. I will direct these three discussions towards Vladmir Putin’s written remarks on the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Second World War (Putin, 2020), Marlene Laruelle’s work on the rise of fascism in Russia (Laruelle, 2021), and motivate an argument not just for memory as a political end, but for the end of memory.

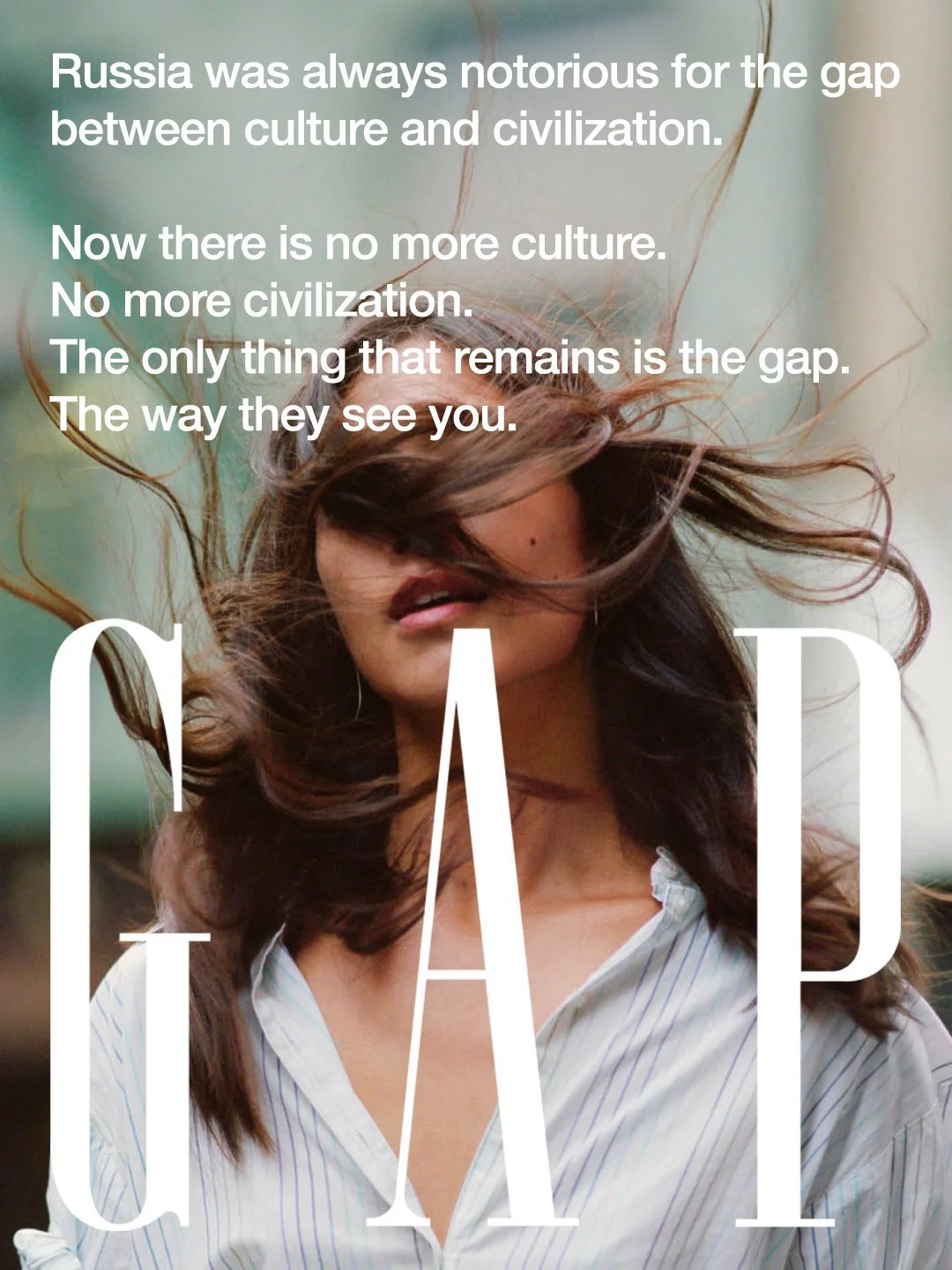

Firstly, in the 1990s, Russia was coming to terms with its new post-Soviet capitalist reality. It seemed as if all countries had finally aligned along similar goals of prosperity and democracy, and real-world conflict had given way to softer agitations of economic, political, and cultural hegemony. A point which Francis Fukuyama described as arriving at ‘the end of history’ (Platt, 2022a). In the collapse of state socialism, the world had lost its last grand narrative, and developed a postmodern incredulity towards metanarratives (Lyotard, in Platt, 2022b). But faith in shared national political histories was far from lost in post-Soviet Russia, where a population anxious about the future of its civic identity created a psychological vacuum within which the limbic weaponization of narratives about the past roared back in the form of postmodern political performance.

Fueled by the assertions of political technologists, Russian politics under Putin has engineered a system of total political rule. Where everything from viable opposition to foreign policy is completely stage managed. There has been a targeted ideological rehabilitation of Russia’s role in the Second World War in renewing Russia’s perception of itself as a geopolitical force, with Putin as solar locus around which these memories orbit. Putin’s postmodern simplifying of past achievements and reframing of the past as positive nostalgic force has supported and drawn upon a simulacrum of democracy (Platt, 2022c), and are ‘attempts to use historical narratives as an instrument of domination and symbolic violence’ (Bergmane, 2020). This metanarrative identity vacuum has motivated a political reassertion of control over Russian civic identity, where Putin’s administration has sought to mold collective civic memory into a selective nostalgia for a glorious, but questionable past.

This vacuum of anxiety towards a civic future was filled by the reclaiming of certainty in the past, even if, as Putin has demonstrated, that past is treated as malleable. The plurality of truths and political positions which accompany such reclamations have created a Russian civic identity and society of managed, total, irony. Especially in Putin’s control of televised media, which has increasingly limited its scope and societal communications, and highly managed approved narratives of Russia’s perspectives and actions (Platt, 2022d). Media voices seeking to speak truth to power have either been censored, shut down or moved abroad, and the grand state narratives of the past discredited or rehabilitated for modern political ends. With the re-establishment of vertical power under Putin and increasing reassertion of centralized control over the regions, both media, messaging and on-the-ground military action have worked together to reclaim a previously held position of Russia unity and brought forward the question of national identity. In doing so, collective memory has been closely controlled. If the medium is the message, then the message is one of selective memory.

Whereas the former Soviet Republic was regulated by a ‘friendship of peoples’ (Putin, 2020) in the post-Soviet era, nationalism now represents a complex and diverse set of ethnic identities. Putin’s stance through this has been highly nuanced (Platt, 2022e), both suppressing ethnonationalism and branding opposition as extremist and increasingly, fascist. In doing so, weaponized memory has been a key tactical instrument. And while attempts by the Russian State Duma to create new definitions of Russian civic identity have proven conceptually difficult (Platt, 2022e), the roiling threat of ethnonationalist violence still bubbles beneath the surface and has exploded with disastrous effect in the current conflict in Ukraine, where a fascist narrative has emerged for any divergent group, especially those seeking closer ties to NATO and the European Union.

Secondly, in stitching together this patchwork of civic values and national identity, Putin has repeatedly turned to the restorative events of the past to illustrate ‘such values as selflessness, patriotism, love for their home, their family and Motherland remain fundamental and integral to the Russian society to this day. These values are, to a large extent, the backbone of our country's sovereignty’ (Putin, 2020). Under Putin, history has returned as a means of more insistent promotion of Russian interest. One in which geography, particularly the relationship with the West, is used as the definitive lens through which to look back. These grand narratives reclaiming previous geopolitical influence have resulted in increased political agitation. The ‘bright, civilized future’ which Yeltsin spoke of in 1999 (Platt, 2022a) is very different from the matrix of historical and political realities under Putin which the Russian people actually got.

As German social memory scholar Aleida Assmann articulates, the future ‘no longer appears to us as a sort of El Dorado of fulfilled hopes and desires. Rather, it has become the object of our ceaseless worry’ (Assmann, in Platt, 2022f). Particularly within liberal societies as climate change, economic uncertainty, political turmoil, identity politics and the erosion of previous social structures continue to coalesce into an increasing psychological threat of impeding catastrophe. This is not an exclusively Russian phenomenon, but post-Soviet focus on memory, collective trauma and how the path forward is shaped by the unique historical reclamation of the past being driven towards increasingly extreme nostalgic rhetoric, and a ratcheting up of foreign tension.

For Putin, ‘Historical revisionism, the manifestations of which we now observe in the West, and primarily with regard to the subject of the Second World War and its outcome, is dangerous because it grossly and cynically distorts the understanding of the principles of peaceful development, laid down at the Yalta and San Francisco conferences in 1945’ (Putin, 2020). But this revisionism isn’t just happening in the West. Russian state rehabilitation of the Soviet past has been highly selective, with a particular focus on The Second World War, and aches for lost Soviet geopolitical greatness. A call for the world to acknowledge the collective sacrifice performed by the Russian people in defeating fascism (Putin, 2020). Putin’s rhetoric of reclamation talks of the torment and hardship endured, of perseverance and sheer, unbending willpower to win. That ‘what they shared was the love for their homeland, their Motherland. That deep-seated, intimate feeling is fully reflected in the very essence of our nation and became one of the decisive factors in its heroic, sacrificial fight against the Nazis’ (Putin, 2020).

If the Yeltsin years were founded on staunch rejection of the torment of the Communist past, the Putin era works to transform that traumatic past into a source of collective strength. Of overcoming the threat of fascism and saving the world. These politicized memories have been reassembled into one of Russian nationalist greatness since the start of the 2000s. Instead of rejecting the Soviet past, the overwhelming state narrative has been one of selective pride. It’s the Russia of great artistic, technological, military, and societal achievement over the brutal mass collectivization campaigns under Stalin, the human made famines of the Holodomor, or the torture of the Gulag (Platt, 2022f). As Yeltsin himself neatly describes, ‘of course, one might have avoided some things, or softened others. But on the whole, the mass repressions, harsh political monopoly, class-based purges, total ideological weeding out of culture, isolation from the external world, and support of an atmosphere of antagonism and fear, all of these are the characteristic features of the totalitarian regime’ (Yeltsin, in Platt, 2022f).

If Yeltsin’s nostalgia was a scene of trauma, Putin’s is an object of proud reminiscence which serves to remind the Russian people of their unique position in overcoming the uncertainty and anxiety of the future. But in doing so, Putin has had to reframe specifics, and bend collective memory to fit such narratives. In 2019, the European Parliament voted to condemn all totalitarianisms, indirectly associating Nazism with Communism (Putin, 2020). As Laruelle describes, ‘Putin felt obliged to denounce this “unpardonable lie” about the parallel between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany and expressed his disapproval. ‘Attempts to distort history do not stop. Not only by the heirs of Nazi accomplices, but now even by some totally respectable international institutions and European structures’ (Laruelle, 2021). She asks, ‘who are the new fascists advancing a revisionist interpretation of the Second World War today: Putin’s Russia or the Central and Eastern European countries?’ (Laruelle, 2021).

Since the early 2000s, remembrance of Soviet victory over fascism has been framed as integral to modern Russian norms. The seed from which positive post-Soviet life thrives. That such triumphs and tragedies are ‘an inalienable part of our thousand-year long history’ (Putin, 2020). And it’s not just a matter of domestic political culture. It’s increasingly framed agitated foreign policy. Putin has sought to reframe the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939, a non-aggression treaty between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, the existence of which was ardently denied by successive Soviet administrations until 1989 (Platt, 2002g). The notion of Germany and the Soviet Union creating distinct spheres of influence and cynically carving up Eastern Europe had been all but officially erased from Soviet memory, despite its publication in the West. Lithuania, and Western Poland were attributed to Nazi Germany, and Bessarabia, Eastern Poland, Latvia, Estonia, and Finland to the USSR. Lithuania was later exchanged against several Polish territories, ending up in the Soviet sphere (Bergmane, 2020).

Putin has used the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact to motivate a position where the Soviet Union had no alternative but to act, reluctantly drawing them into the war in the face of lack of help from their western allies. ‘It was only when it became absolutely clear that Great Britain and France were not going to help their ally and the Wehrmacht could swiftly occupy entire Poland and thus appear on the approaches to Minsk that the Soviet Union decided to send in, on the morning of 17 September, Red Army units into the so-called Eastern Borderlines, which nowadays form part of the territories of Belarus, Ukraine and Lithuania’ (Putin, 2020). While Putin’s original statements of the early 2000s actively acknowledge the cynical nature of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, his more recent statements have sought to reframe memory of the same actions as driven more by defensive, selfless motivation. This is Putin shaping collective memory, rather than rehabilitating history, molding Halbwachs’ ‘collective current of continuous thought’, retaining from the past only what still lives or is capable of living in the consciousness of the groups keeping the memory alive (Halbwachs in Platt, 2022g).

Finally, Putin talks of ‘inheriting the feat of the warriors of our homeland that defended it during the Great Patriotic War’ (Putin, 2020), but he’s not alone in doing so. Restorative nostalgia is a global trend, closely associated with Donald Trump’s 2016 ‘Make America Great Again’ and Brexit’s ‘Take Back Control’. Such malleable nostalgic populism for a selective past which likely never was provides powerful political rhetoric and emotional patriotism for those who feel left behind by the liberal progression of the past fifty years. Such post-truth slogans don’t just weaponize memory as a political end but call memory into question, and what’s considered recorded history itself (Halbwachs in Platt, 2022g). Recently, this has turned memory into actual war. For Russians, fascism represents the ultimate evil (Laruelle, 2021). That the existential fight against Nazi Germany was, and still is, a struggle for Russia’s very survival. The association of fascism with the Soviet Union by the European Parliament, combined with the continued expansion of NATO pose an equally modern existential threat. ‘The mere suggestion that some Soviet or Russian citizens might take a positive view of fascism is offensive to the majority of the public. Fascism is considered a uniquely Western-produced phenomenon, totally foreign to any Russian traditions, and one that can only appear on Russian soil as an import from the West’ (Laruelle, 2021). This isn’t just a subversion of Fukuyama’s end of history and return to grand narrative, it’s the weaponized rhetoric of the end of collective memory itself.

Russian state media, in combination with the rhetoric of Putin’s political rallies and public writings, have increasingly framed agitation from both the West and those who would seek to join them, as fascist. There have been accusations of Ukrainian ‘genocide’ in Eastern Ukraine, with war crimes in abundance as the ‘special military operation’ escalates. Ukrainians and other dissenting voices have come to describe Russia’s supporters as Rassistii, combining the Russian words for Russia and fascism (Platt, 2022i). Here memory war has turned into real war, with claims of far-right nationalism on both sides, and mutual, intentional discrimination. At the outbreak of the current conflict, Putin declared his aim of the de-Nazification of Ukraine (Platt, 2022i).

Putin holds that ‘Neglecting the lessons of history inevitably leads to a harsh payback. We will firmly uphold the truth based on documented historical facts. We will continue to be honest and impartial about the events of World War II’ (Putin, 2020). Driven by grand collective narrative, the restorative nostalgia inherent in modern Russian politics, which ratchets up agitation to the point where it boils over from memory war into real war is a clear echo of Ernest Renan. That ‘unity is always achieved by brutality’ (Renan, 1882). And that ‘the essence of a nation is that all individuals have many things in common, and also that they have forgotten many things’ (Renan, 1882). The choice of what we are able to remember, what politicized nostalgia seeks to achieve, and what we choose to forget is increasingly malleable, manipulated, and militarized. But if the end of history is behind us, the end of memory is now upon us too.

References:

Bergmane, U. (2020). How Putin is Rehabilitating the Nazi-Soviet Pact. Baltic Bulletin. July 28, 2020. [Digital File]. Retrieved from https://canvas.upenn.edu/courses/1642503/files/107437869/download?download_frd=1.

Laruelle, M. (2021). Is Russia Fascist? Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, pp. 1-9;157-166. [Digital File]. Retrieved from https://canvas.upenn.edu/courses/1642503/pages/readings-3c-nationalism-putins-opposition-or-resource?module_item_id=23426477.

Platt, K. (2022a). Lecture 3A: Putin’s Rise. [Digital File]. Retrieved from https://canvas.upenn.edu/courses/1642503/pages/lecture-3a-putins-rise?module_item_id=23426468.

Platt, K. (2022b). Lecture 1C: Postmodernism and Russian Media in the 1990s. [Digital File]. Retrieved from https://canvas.upenn.edu/courses/1642503/pages/lecture-1c-postmodernism-and-russian-media-in-the-1990s?module_item_id=23426445.

Platt, K. (2022c). Lecture 5C: Putin 2.0. [Digital File]. Retrieved from https://canvas.upenn.edu/courses/1642503/pages/lecture-5c-putin-2-dot-0?module_item_id=23426516.

Platt, K. (2022d). Lecture 4A: Media in the 2000s. [Digital File]. Retrieved from https://canvas.upenn.edu/courses/1642503/pages/lecture-4a-media-in-the-2000s?module_item_id=23426482.

Platt, K. (2022e). Lecture 3C: Nationalism: Putin's Opposition or Resource. [Digital File]. Retrieved from https://canvas.upenn.edu/courses/1642503/pages/lecture-3c-nationalism-putins-opposition-or-resource?module_item_id=23426476.

Platt, K. (2022f). Lecture 4B: Between Trauma and Nostalgia: Post-Soviet Memory. [Digital File]. Retrieved from https://canvas.upenn.edu/courses/1642503/pages/lecture-4b-between-trauma-and-nostalgia-post-soviet-memory?module_item_id=23426486.

Platt, K. (2022g). Lecture 8B: Other Histories. [Digital File]. Retrieved from https://canvas.upenn.edu/courses/1642503/pages/lecture-8b-other-histories?module_item_id=23426544.

Platt, K. (2022i). Lecture 6C: Memory of War, War of Memory. [Digital File]. Retrieved from https://canvas.upenn.edu/courses/1642503/pages/lecture-6c-memory-of-war-war-of-memory?module_item_id=23426520.

Putin, V. (2020). The Real Lessons of the 75th Anniversary of World War II. The National Interest. June 18, 2020. Retrieved from https://nationalinterest.org/feature/vladimir-putin-real-lessons-75th-anniversary-world-war-ii-162982.

Putin, V. (2022). For a world without Nazism. Crimea Rally March 2022. [Digital File]. Retrieved from https://canvas.upenn.edu/courses/1642503/pages/for-a-world-without-nazism-crimea-rally-march-2022?module_item_id=23693138.

Renan, E. (1882). Qu'est-ce qu'une nation? et autres essais politiques. Paris. Presses-Pocket. Translation Ethan Rundell (1992). [Digital File]. Retrieved from http://ucparis.fr/files/9313/6549/9943/What_is_a_Nation.pdf.

Befores, Beginnings and Boundaries

Soviet heteronormative masculine transition in Sergei Bodrov’s Prisoner of the Mountains

“The short-lived culture of optimism and limitless opportunities was over. A culture of pessimism and cynicism set in.”

(Sandfort & Stulhofer, 2004)

The introduction of the two protagonists of Sergei Bodrov’s 1996 Prisoner of the Mountains can be read as representative reflection of differing states of masculine gendered performance transition during the post-Soviet transformation of the early nineties. Ivan and Sacha are the same Russian male, but at different stages of evolution and adaptation. Ivan is the familial-oriented, optimistic, and hopeful boy of the period immediately following the collapse of state socialism. Sacha the cynical, confident Russian man which swiftly results.

We open on a distant rural exterior shot of a truck loaded with men moving left to right as black smoke of an unknown origin rises on the horizon. Triumphant military music is heard in the distance. The camera pans from outside to inside, and as our eyes adjust to the changing light, they’re also tested with an optical examination and the echoes of a patient slowly reading off the letters of a Snellen chart. The doctor, distracted, multitasks the examination over lunch and orders “cover your right eye”, where the camera cuts to a close-up of a young male patient, Ivan, switching a paddle from his left to right eye. He continues to read as the nurse counts off the rows of letters with a stick.

As Ivan begins to strain, the optician leans in for a closer look, ends the exam, and marks his paperwork in close-up as ‘fit to serve’. Dismissed with “there’s no use sitting here”, the camera follows Ivan in his role as naked proto soldier as he exits into a sterile corridor, where he is joined by other naked young men, who homogenously cup themselves and walk briskly behind a female nurse. Some of them smile and the air hums with awkward, anxious conversation. They round the corner into a new room where others just like them are being weighed, measured, and evaluated. One anonymously asks “Comrade Major, where will we be stationed?” The barked response “wherever your country sends you” ends the conversation before it begins.

The young men bunch and form a line, their flesh blurring together in front of a tired, seated doctor who is performing physical evaluations. Ivan is instructed to sit up, sit down, rotate, and respond to the doctor’s requests. His genitals are examined. It tickles. Again, a paper is signed.

A starkly sharp cut from the sterile white interior space of the infirmary takes us to the dark, headlit point-of-view exterior of a closed border gate, where we jump in time as well as visibility and familiarity. As the gate creaks open, an off-camera voice yells “wake up, guys!”. The headlights illuminate the face of Ivan, who is now an armed soldier. We switch from the first-person view of the front of the truck to a reverse shot of an older soldier, perched on the truck’s front bumper, whistling. A carton of cigarettes and a bottle of vodka weigh down his disheveled, unbuttoned military fatigues. As the truck passes a tank covered in relaxing soldiers, the carton is thrown to them with the salutation “here is your grenade!”

The truck arrives back at camp, our older protagonist jumps off, and announces his return to a commanding officer, who idly plays billiards and drinks outside under a floodlit table. The contraband vodka is opened and poured directly into the officer’s cup which nestles conveniently in the center pocket. The two toast to their health, and as voices swell in the distance, our returning protagonist asks, “why are they shouting?” before picking up his AK-47 and firing into the barracks. We are treated to a slow close-up of the rifle barrel as it unloads, and an even slower pan up towards the laughing, delighted face of Sacha, our second protagonist. A subdued, solitary voice begins to sing, the chess pieces now introduced, and the scene is set for the film to begin.

Sacha and Ivan are men of contrast. Sacha’s confident, worldly, careless, and connected. An individual. Ivan’s nervous, inexperienced, hopeful and one of a faceless collective. Sacha whistles as gates open for him, returning favors with contraband and intimate with authority. Ivan is lost in the background noise, his youth homogenized into the soup of required civic military service against ethnic agitation. Sacha’s been in the world for years, Ivan’s only just emerged from the sterile womb of training, still the raw material being shaped from boy to man and leaving the cocoon of the state.

We can read Ivan and Sacha as the same individual in different stages of post-Soviet masculine evolution. If Ivan is the youthful, immediate post-collapse enthusiasm and hopeful promise of perestroika, Sacha exhibits the highly individualized resilience, adaptability, and connection towards which Russian men needed to transition (Pesmen, 2000). The boundary of being able to thrive in the resultant unfamiliar new culture of capitalism, commercialism, and updated means of gender roles, responsibilities, and performance (Platt, 2022). Ivan is the hope of a brighter future, perhaps the future Russia deserves. Sacha’s the future Russia actually gets.

Notions of masculinity changed drastically in early nineties Russia, where definitions of maleness adjusted to one’s ability to navigate a new commercial reality and build economic capacity (Platt, 2022). The ‘new uncertainty and increasing hardships pushed men into a masculine anomie’ (Sandfort & Stulhofer, 2004). To be able to defend one’s interests, often with corrupt and violent means. Sacha’s complicit in his corruption, but his criminal behavior is visibly tolerated, and the strength of his relationships even permit him to fire on his own men. Sacha starkly reflects the early nineties’ increased individualism ‘often synonymous with embezzlement, materialism and cynicism’ (Sandfort & Stulhofer, 2004).

Ivan and Sacha are different points on the same timeline of masculine maturity inside of the post-Soviet transitional era. Ivan as representative of that briefest of moments where optimism, hope and the release from state socialism brought the promise of a prosperous, thriving future. And Sacha as personification of post-collapse krutit’sia (Pesmen, 2000), relational intimacy, commercial corruption, cynicism, and confidence which prevailed in a new culture of male anomie. Bodrov’s film has the optimistic and resourceful Ivan prevail, and the cynical Sacha murdered at the hands of ethnic rebels. A commentary in 1996 of a positive future perhaps not entirely lost, and still within grasp in the near history of the past.

References:

Bodrov, S. (Director) (1996). Prisoner of the Mountains [Film]. Orion Classics.

Pesmen, D. (2000). If You Want To Live, You’ve Got to Krutit’sia: Crooked and Straight. Russia and Soul. Cornell University Press. pp. 189–207.

Platt, K. (2022). Lecture 2A: "Race, Ethnicity, Gender". [Video file]. Retrieved from https://canvas.upenn.edu/courses/1642503/pages/lecture-2a-race-ethnicity-gender?module_item_id=23426453.

Sandfort, T. & Stulhofer, A. (2004). Introduction: Sexuality and Gender in Times of Transition. Sexuality and Gender in Post communist Eastern Europe and Russia. Routledge. 2008. pp. 37-60.

Beanpole’s Frozen Trauma

The icy Leningrad wind blows through the soulless, gray buildings. The equally soulless, gray people recovering from the immediate aftermath of The Second World War blow through the streets like torn pieces of newsprint. These frigid streets mask the squalid desperation of those who’ve survived, and look to make the transition into what will become the post-war Soviet socialist state. It’s a moment beautifully frozen in time, but also the moment we first meet Iya (played by the incredible Viktoria Miroshnichenko), frozen in place not by the weather, but by the temporary immobility of post-concussion syndrome. Her voice in close-up crackles and she trembles as her muscles spasm. All we hear is a distant ringing, and the drowned voices of the blurred figures she works with in the infirmary. The shot uncomfortably lingers. We are forced to watch ever closer, increasingly drawn into her suffering.

As the ringing subsides, Iya recovers her composure, and returns to the world, free of her temporarily emotional and incapacitating bondage. She towers over her nursing colleagues, earning her the eponymous nickname Beanpole, where she works in an infirmary to care for a small number of injured Russian soldiers, recovering from their time at the front. Some are injured in highly visible, graphic ways. Others are more injured in ways we can only imagine. As she goes about her daily routine between work and home, we find she cares for an undersized three-year-old boy, Pashka, who is not only underdeveloped physically, but also emotionally, having been born on the Russian front to Iya’s close friend Masha (played equal to Miroschnichenko’s excellence by first time actress Vasilisa Perelygina), who is set to return from the advance on the Russian front in Berlin.

As small as he is, Pashka is an enormous source of pleasure for Iya, as they play around the tiny apartment. Pashka visits the patients, where they struggle to play charades with him as he struggles to identify the animals they imitate. As Iya cares for Pashka one evening, they chase each other around their squalid apartment, and collapse on the floor as Iya cuddles and hugs Pashka tightly. But all is not well. The ringing eerily emerges from the distance, Iya freezes, and in one of the most incredibly touching but terrifying scenes, smothers Pashka to death. As with much Russian cinema, the cinematography is breathtaking, but fearless about taking its time to adequately tell the story. The shots linger, the silences draw out, and the agonizing last gasps of the smothered child are held uncomfortably long as we too hold our breath in the audience. It’s an incredibly powerful treatment of a sincere love gone disastrously wrong.

A few days later, Masha arrives to stay with Iya, and in the darkness of her arrival, asks where Pashka is, learning of his fate, although Iya hides the exact details and her own culpability. Eager to replace Pashka, Masha becomes swiftly determined to conceive at any cost, even though she’s physically no longer able to do so after the abuse of several brutal abortions. We are witness to the large scars on her stomach and the intimate details of her infertility. Joining Iya as an orderly in the infirmary, we learn a little of their backstory, and find that they were both gunners on the Russian front, and when Iya was invalided out, Masha fought on, eventually fighting in the liberation of Berlin. She’s decorated for her efforts, but performs menial work in service of the often helpless patients. One in particular seeks to be euthanized, and when the head Doctor Ivanovich (Andrey Bykov) refuses, Iya steps in and performs the necessary duties. But she’s seen by Masha, who uses the opportunity to blackmail Ivanovich into sleeping with Iya in order for her to have another baby of her own. Against their will, both Iya and Ivanovich awkwardly, and unsuccessfully attempt to conceive, as the highly introverted and sexually immature Iya grows increasingly jealous of a real relationship Masha is developing with a local boy, Sasha.

As Iya finds out she’s not pregnant, Masha tries on a dress a neighboring seamstress has made for her. As she twirls over and over, she turns from joy to anguish, unable to stop her spinning, and the twirls turn to terror, to which Iya grabs Masha and kisses her to calm her down. Masha begins to fight Iya off, whereupon the ringing returns, and there’s an awful echo of Iya, laying on top of Masha, experiencing an episode and in further danger of killing not just Pashka, but also his mother. Masha initially fights her off, but ends up passionately kissing her back before freeing herself. It’s in this moment we realize their intense love for each other, even though they want different things. Masha is desperate for motherhood. Iya wants mastery over Masha at any cost. The movie ends with the two of them embracing and weeping together, resolved to their different sources of pain, their lives highly braided together.

Suffering runs throughout Beanpole in many forms. The physical suffering of the patients and the smothering of Pashka. The raw scars of Masha’s stomach and the frozen stasis of Iya’s episodes. The devastating emotional trauma of war, especially upon women who served, and the equally emotionally scarring events of lost children. Of lives shattered by the horrors of the front line.

But efforts to ease the suffering are rarely effective. The euthanization of the paralyzed soldier results in more guilt for Iya and the blackmailing of Ivanovich. Masha’s desire to ease her suffering of the loss of Pashka results in the rape of Iya by Ivanovich as Masha lies next to her in the bed. The characters are desperate, and cling to life and each other for all they’re worth. And it’s all captured in its lingering intimacy with exquisite cinematography, long individual shots, and the microscopic attention to detail that only comes from seeing this kind of pain in close up and for longer than one wants.

Beanpole is phenomenal. Not just for Kantemir Balagov’s expert directorial work, or Ksenia Sereda’s wonderfully tender and equally brutal cinematography, or the patient, intricate, intimate editing from Igor Litoninskiy. But for the two incredible performances from Viktoria Miroshnichenko as Iya and Vasilisa Perelygina as Masha. Both roles draw you into their claustrophobic, desperate, painful lives, and as the suffering gets woven together, especially as Iya’s feelings for Masha become physical, the brutality of the Leningrad winter is no match for the warmth created between the two women. A warmth which, as the credits roll, gives us hope that their frozen suffering is finally drawing to a close.

Beanpole is available to rent on Amazon Prime Video.

Auspicious Advertising: The Russian Thirst for Reincarnation

“The picture was so heavily loaded with symbolism that Tatarsky couldn’t understand how the thin aluminium of the can could support it.” (Pelevin, 1999a)

Babylen Tatarsky’s creative ascent in the advertising world parallels his accelerated descent into substance abuse. In this malleability of reality into what will ultimately become his great ‘Russian idea’, we find two stark illustrations of the increasing weaponization of media. His encounter with a can of Tuborg pilsner in search of relief from a hangover, and Hussein’s torturous video loop of a soldier being killed. Combined, they serve as symbols for the quenching of thirst for true national Russian unity. In the solace of the can of Tuborg he finds the hopeless symbolism of a present national journey leading nowhere, a thirst unquenched. In the murderous mantra of the video loop, he finds only relentless consumption of the product offers the high and auspicious reincarnation and nationalist quenching he’s promised by Gireiev (Pelevin, 1999b). The product advertised is endless ethnic conflict.

Tatarsky is coming down from a revelatory, hallucinogenic, alcoholic nightmare, and in search of immediate cure for a raging hangover. He awakens to a crisp, fresh Moscow morning. The kind of glorious start to the day which makes hangovers worse. Absorbed in thought and his mind increasingly consumed by both the creative process and as much vodka as possible, he leaves home seeking nearby relief.

His usual morning-after tonic is ten minutes away at the round-the-clock (or as the local drinkers refer to it, the round-the-bend) shop, which proves too far. The kiosks of his professional life prior to advertising are nearer, even if they mean an ethical and medicinal roll of the dice. Tatarksy buys three cans of Danish pilsner Tuborg, and what Pelevin refers to as an analytical tabloid. But Tatarsky’s interested in neither the news nor the analysis. He’s there for the creative calamine of the advertisements.

A large advert for Aeroflot catches his attention, albeit in a negative way. It depicts a married couple in an aspirational, heavenly tropical setting, but Tatarsky feels the ad thirsts for more realism and practicality. He conjures the perception the ad promises to fly passengers to Novosibirsk, but really takes them to heaven. As he concludes to himself, “might as well invent an Icarus airbus” (Pelevin, 1999). A comment not only on the efficacy of the advert, but also perhaps on the health of the airline itself.

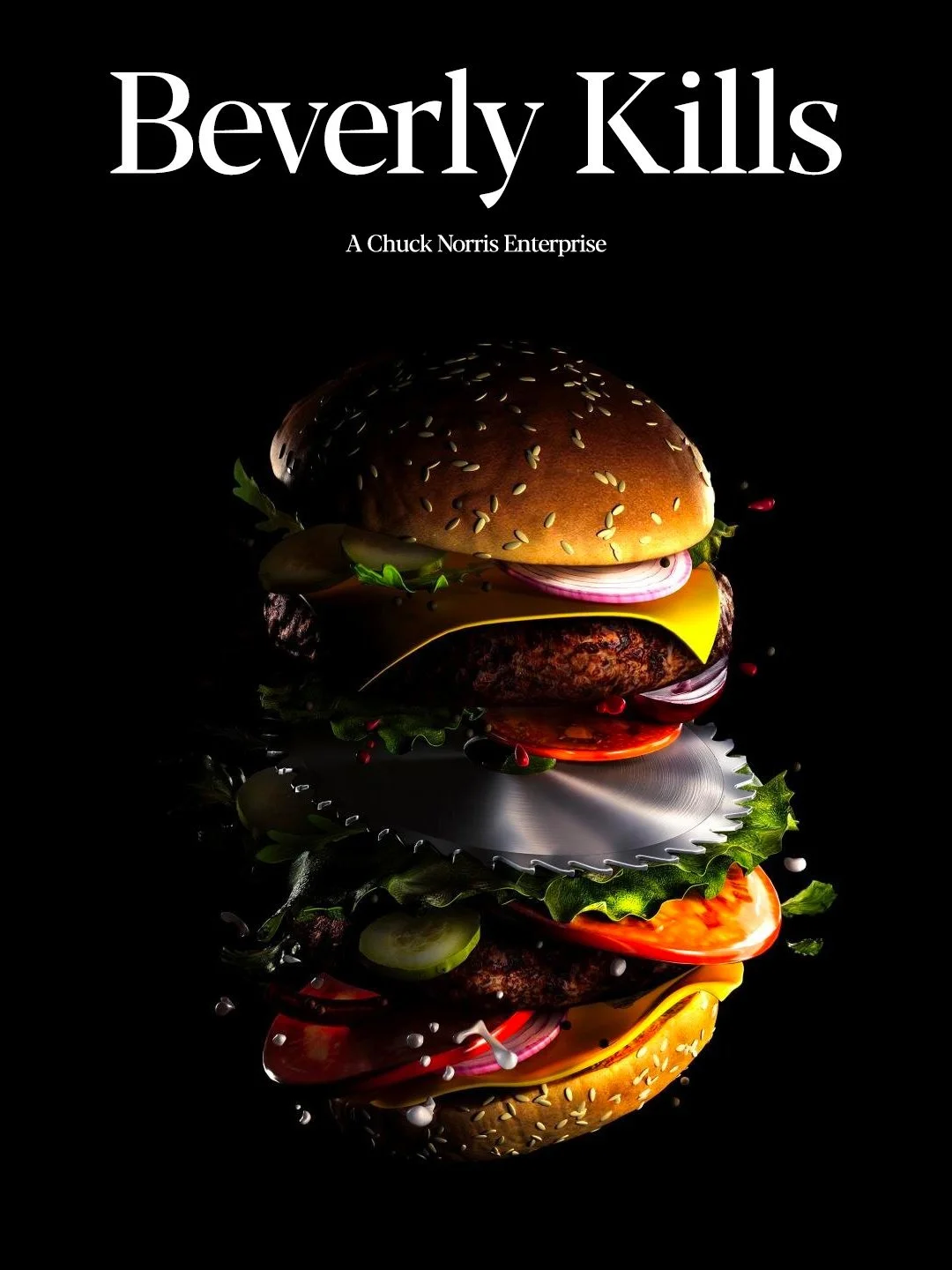

His attention is further caught by a colorful ad for an American restaurant on Uprising Square, a vivid contrast of east and west. The restaurant, daubed in neon signage is perhaps menacingly named ‘Beverly Kills’, and supported by action star Chuck Norris. We imagine they serve a lot of red meat to eager Russian diners looking to consume the offal of the west over drinks and supper.

Still nursing his hangover, Tatarsky uses the newspaper for comfort by sitting on it, continuing to drink his Tuborg. He meditates on the Tuborg can’s illustrative design. An overweight, exhausted, thirsty, suited man wipes his brow with a white handkerchief on a bright, sunny day as the path he’s on trails off into the horizon. Inspired by Danish social realist Erik Henningsen’s original illustration (Oakley, 2018), and unable to turn off his internal creative process, Tatarsky begins to compose slogans for Tuborg. Like the nightmare he’s recovering from, he sees the Tuborg path as one of spiritual enlightenment, even though it leads nowhere except death. Everything in the present is empty and meaningless until the end. In the white handkerchief we find symbolism of broader national surrender of hope in the face of increasing western commercialism from the exhausted traveler, with the equally unhealthy hangover in the real world from state socialism as it takes the path into the distance. Tatarsky first concludes with the more hopeful slogan ‘Prepare yourself’, then revises it to the pessimistic variant ‘Think final’ (Pelevin, 1999a). He leans on his fondness for Latin slogans but struggles to remember the specifics. Eager to capture the moment, he rummages through his pockets to find a pen, without success. The idea, like the bubbles in the beer, and perhaps the very notion of a commercial Russian reality, will evaporate into the ether.

The creative moment is short lived, replaced by fear. Hussein, the local kiosk krysha (Ries, 2002), and like Tatarksy, ‘surfacing from a recent fix’, a short, ethnic astrakhan hat on his head, arrives and makes Tatarsky an offer he can’t refuse. Tatarsky, in terror, drops his beer, which traces out in a yellow stream, and a very different kind of abject relief. As he’s led away to Hussein’s nearby trailer, Tatarksy follows the same meaningless path of finality as the exhausted Tuborg avatar, yet with little promise of enlightenment. As Hussein says ‘come on’, Tatarksy considers running, but thinks better of it.

Inside Hussein’s trailer, with its thick curtains and precarious green satellite dish, a television illuminates a half-dark room. A VCR, set to pause, depicts the murderous throat-slashing finale from Bodrov’s ‘Prisoner of the Mountains’ (Bodrov, 1996). Chained to a table, forced to watch the horror on repeat, is an unshaven man in a crumpled jacket with gold buttons. His mouth is bound but on the tape is drawn a large smile in red marker. The emotional and physical torture, perhaps like all the best advertising, is masked by synthetic happiness. Tatarksy’s mind wanders to the captive being in the same position as the protagonist of a recent Korean Air advert. Hussein waves his mobile phone in the direction of the hostage to indicate if the man is ready to make a call. He is not.

Resigned, Hussein presses play, and the carnage murderously loops again. Tatarksy, his mind still consumed by media, thinks it’s a promotional video, where the message is repeated over and over until the consumer has no choice but to commercially submit. The aggressors in the clip are wearing the same ethnic hats as Hussein, suggesting he will do the same to the captive if co-operation isn’t forthcoming. The torture of the man we later find out to be someone a rival kryshi are looking for, leads nowhere. The locus of any quenching is slit. The phone call is never made, the loop endlessly cycles, and the drinking continues.

The symbolism of an endless, hopeless loop of perpetually reincarnated ethnic conflict, weaponized for commercial ends and the quenching of national aspiration is stark. If the Tuborg traveler is on a path to enlightenment which never arrives in the present, such enlightenment might just be gained by the endless consumption of advertising in the future. Watch long enough and you will believe in anything we tell you, even perhaps reincarnation in the form of computer-generated avatars artificially running the country.

The sequence acts as a fulcrum around which Tatarsky’s reality tips from playful commercial wordsmith to social and psychological agitator. He moves from speculation about better ads for beer and travel to existential dread at the loss of national hope and the quenching remedy of endless ethnic conflict. But in doing so, Hussein inadvertently offers a way out, a mantra of consumption which foreshadows the menacing political future Tatarsky’s about to enter.

References:

Bodrov, S. (Director) (1996). Prisoner of the Mountains [Film]. Orion Classics.

Oakley, H. (2018). Erik Henningsen: The Thirsty Man. The Eclectic Light Company. Retrieved from https://eclecticlight.co/2018/05/24/erik-henningsen-the-thirsty-man/

Pelevin, V. (1999a). Homo Zapiens. Penguin Books. p. 129.

Pelevin, V. (1999b). Homo Zapiens. Penguin Books. p. 126.

Ries, N. (2002). Honest Bandits and Warped People: Russian Narratives about Money, Corruption, and Moral Decay. Ethnography in Unstable Places: Everyday Lives in Context of Dramatic Political Change. Durham, N. C.: Duke University Press. p. 276-315.

Week 1 Reflection

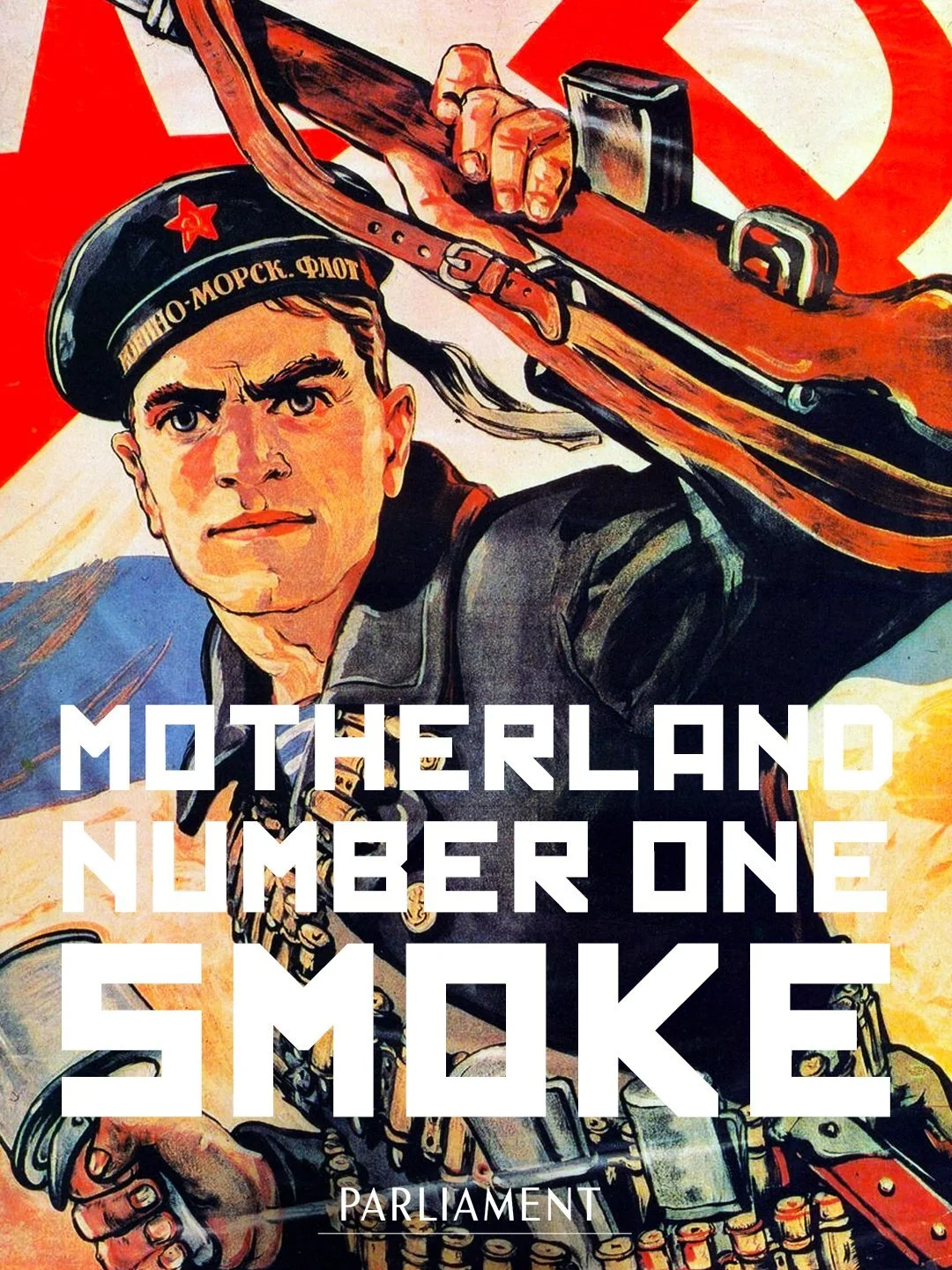

Tatarsky’s advertisement for Parliament cigarettes exemplifies Pelevin at his most mischievously postmodern and playful. Ironically remixing and recycling events from recent Russian history to provide a masked commentary hidden within the commercial language of the hard sell.

The poster itself depicts a photograph of the Moscow River taken from the bridge near where Yeltsin and his supporters stood down the oncoming tanks during the Putsch of August 1991. But also, the same site two years later in October 1993 where Yeltsin dissolved the Supreme Soviet and ordered the same tanks to fire upon the Russian White House. The former parliament building, up in smoke like its smooth filtered namesake, is replaced in the ad by a building-sized pack of Parliament cigarettes, surrounded by palm trees. The slogan, a quote from Griboedov’s 1825 satirical play proclaims, ‘Sweet and dear is the smoke of our Motherland’.

Pelevin ironically mixes the contradictory political events of 1991 and 1993 with the increasing commercialism entering the former Soviet Union. As the cigarette goes up in smoke as the citizens of the Motherland enjoy the moment, so does the former establishment as represented by the seat of the Supreme Soviet under shelling from Yeltsin’s military. The democracy Yeltsin so passionately defended in 1991 has been burned. The air is sweet and dear with the cost of lives. The palm trees which surround the White House are also no accident. They’re Pelevin’s commentary on the Russian Republic transitioning to a Banana Republic, where the quick and the lucky flourish, the black market runs rampant, and the nefarious diversion of goods oils the economy. It’s a nod to Russia’s imminent future but uses the language of the Soviet past.

As Tatarsky completes his work, he gloomily thinks to himself ‘thou lookest out always for number one’, which characterizes not only Yeltsin’s dogged political survival, but also the new culture of krutit’sia which emerged in post-Soviet Russia, with every person for themselves screwing as much as they can out of each other and the system, whatever the cost. The old symbols of authenticity and authority are gone, abruptly replaced by both political and commercial brute force using the burning cocktail of artillery shells and nicotine. Sweet and dear indeed.

Week 2 Reflection

The best moments in movies are when they peer into a nation’s soul, hold up a mirror, and reflect who we truly are. Our greatest hopes and aspiration for the future, but also our deepest fears and weakness.

This is the sentiment which motivates Sergei Bodrov Jr.’s national popularity based on his films Prisoner of the Mountains (1996) and Brother (1997). Taken together, in both films Bodrov Jr.’s characters reflect the contradiction of disoriented innocence and resourceful resilience of young Russia. In doing so, they break the traditional stereotype of both krutit’sia and krutoi. They’re crafty and resourceful, putting krutit’sia to work towards near exclusively positive ends. They’re seen to make bombs and pistol silencers just as much as they fabricate toys and fix watches. They’re strongly family-oriented, caring for a brother and writing to a mother. They’re protective of the defenseless, especially towards women, where we see Brother’s Danila avenge Sveta’s abuse and Prisoner of the Mountains’ Ivan befriend Dina, a kindness which saves his life. They’re both bandit and soldier with a strong sense of where the ethical line is, and in which direction their moral compass points. They take from the rich and at least try to give to the poor. They do a lot of bad things, but for the right reasons, a trait we may perhaps even extend to Putin himself.

But the characters are also proud patriots, to the point of prejudice, racism, and national chauvinism, with no love for the west or its perceived invasive culture. They’re heterosexual but not overtly macho, although many they encounter are, with both roles actively subverting the image of the thug, strongman or krutoi, providing not just a physical contrast, but also an ethical one. An atypical image of Nancy Ries’ honest bandit. No fancy car, sharp suit, gaudy jewelry, tattoos, or entourage. They operate in the limbic space between kryshi, protecting the weak, befriending the young, and putting all their resourcefulness and grit to work in service of what they believe to be the right Russian way.

So in holding up a mirror to Russian culture in the late nineties, Sergei Bodrov Jr.’s two films exemplify the best in Russian values. Family, nation, resourcefulness, protection, unity, rejection of the west, and an understated innocence which belies tremendous confidence in his characters’ own capacity to survive.

Week 3 Reflection

Endemic mistrust, malleable narrative and strongly gendered power structures characterize Pavel Lungin’s 2002 film Tycoon, holding a mirror up to post-Soviet oligarchy, and how absolute power corrupts, absolutely. Makovski’s rise in wealth and power is predicated upon the strength of those around him. Their support, friendship, and willingness to participate in his ‘turning of the mill’ of economic subterfuge and sleight of hand. But the inner circle is exclusively a male preserve. Even Mariya, who defects from Koretski’s oppression, symbolic of Soviet-era principles to become Makovski’s lover, never gets to participate in material decisions, and is highly marginalized as an object of entertainment, distraction, and reproduction. Oligarchy is a male blood sport.

At its zenith, Makovski enjoys the adoration and celebration of all around him, who look up lovingly as an orchestra swells at his birthday party. He rides in on an elephant, the master of all he surveys. But even here the cracks are beginning to show. He’s increasingly needing to make problems, and people, disappear. With his increased wealth and power, comes increased risk of corruption and the need to control both relationships and the narratives around him, something we see visibly echoed in contemporary politics around Putin himself.

In his isolation and diminished social cohesion, he physically exiles to France, but also distances relationally as his inner circle begins to unravel in a flood of paranoia and secrecy. Makovski is required to become increasingly self-sufficient, withdrawing from everyone except his wartime consiglieri, Larri, himself an outsider and never truly one of the inner circle due to his Georgian ethnicity. Larri makes Makovski’s problems disappear, while he himself lives in the shadows.

Tycoon echoes a contemporary Russian exceptionalism and isolationism fueled by a perspective of hostility towards anything which doesn’t adhere to a unified national narrative. Makovski’s machismo serves not only as a symbol of national civic identity, able to pull the strings of political power, but also as one for whom social cohesion itself is malleable, with those who’ve made you ultimately being expendable. In this sense, Makovski echoes not only the epitome of Russian oligarchic corruption, but also its fate. As his circle shrinks and expires, all he is left with is a post-modern image of himself, stripped even of his own public narrative of being alive. A hollow shell, stripped of wealth and influence, but even more determined and resourceful as ever. The mill turns.

Week 4 Reflection

Derived from Ancient Greek, nostalgia describes the ache of the desire to return to one’s place of origin. The pain of wanting to be home. The past can be a place of nostalgic longing, but it can also be a place of collective trauma which demands resolution.

The Russian rock band DDT’s ‘Born in the USSR’ mourns the intimate, familial narrative of the Soviet past. It’s ironic, playful, and reflectively comprehends the past as just that, something gone. An irretrievable memory resigned to the half-life of memory. The lyrics sing of lost greatness, orphanage, and sunsets. It’s the nostalgia of time with Grandma and a first kiss. The Beatles, famous for their own song of the USSR, look down upon the proceedings in the music video as a clear symbol of a Yesterday long gone but still strongly alive in the public consciousness.

By contrast, Oleg Gazmanov’s ‘Made in the USSR’ also mourns for a Soviet past, but this time it’s broad and societal, not intimate, or familial. The lyrics ache for former Soviet geopolitical greatness, and appropriate the selective achievements of Gagarian, Lenin, Tchaikovsky, and others. If DDT’s warm reflective nostalgia views the past as fondly lost, Gazmanov’s restorative, anthemic nostalgia seeks to celebrate the present as a proud resolution of the overcoming of trauma from the same Soviet past. A civic identity forged in conflict, hardship, and resilience. As Gazmanov proudly lists off dozens of Russian achievements, he asks us “just tell me something that we haven’t got”. If DDT’s nostalgia locks the past as a memory to be retrieved, Gazmanov unlocks the past as a lens on the present, and the explicit playbook by which to chart an uncertain future.

‘Made in the USSR’ acknowledges the trauma of poverty, the ruin of the church, and the Second World War but recognizes them as sources of pride and patriotism. They are consequences of progress which have been overcome, with the Russian civic identity more unified, stronger, and resolved than ever as a result. It’s not restorative in the sense of bringing something back, it’s articulating the present as if the past never left. That this is who we are as a people. That we are stronger if we embrace and own it, however knowingly selective and exclusive it may be.