ICOM1000

Intercultural Communication

Week 1: What does culture mean to me?

The anthropological approach to culture motivated by Brian Street, shifting a definition of culture from entity to process, helps us understand the essentialist and communal aspects of culture, and the life-giving need to belong to something bigger than ourselves. Culture is something we can have, or belong to, but alternatively from the constructivist perspective, it’s also something we do. If we take these two perspectives of belonging and doing, and apply them to lived experience, I believe we can also explore the notions that there are ritual degrees of breadth and depth to culture. That belonging can be weak or strong. That doing can be active or passive.

When I think of these approaches, I think of my own connection to modern fandom. Either through sports, through the multi-faceted and increasingly fragmented nature of modern popular cultures such as movies, video games or hobbies, or through the communal aspects of supporting a cause.

I am a lifelong Star Wars fan. And when I think of my deep connection to the culture of Star Wars, which has exponentially increased with the internet and our ability to connect to other like-minded souls, I think of the unifying means of belonging and doing as unified through ritual. Here culture is often predicated on seeking out and feeling connected to those who feel the same as me.

If we look at the elements of fandom which are ritualistic in nature, modern fan culture, which we could even characterize as fanatic culture in the extreme, is predicated on a wide variety of highly stylized, repeatable, consistent behaviors, which augment and deepen one’s experience of being a fan, but also connect one’s individual experience to a broader engaged community of those who feel the same, very similar to an experience of faith. Modern fans attend mass gatherings such as comic cons or the premieres of movies, often waiting in line for hours before being allowed entry. We wear clothes which signal allegiance and alignment with our chosen favorite stories, broadcasting to others our preferred avenue and flavor within the culture. We gesture towards each other in specific, ritualized ways as in the Vulcan greeting of Star Trek’s Mr. Spock. We fill our homes with objects and avatars from these stories, which are frequently shrine-like in nature, where we can bask in their collective (and collectible) glow as we re-watch the movies again and again. We quote lines from movies to each other, or casually drop them into conversation, casting out signals for others to join us. We travel to relevant places where we can commune together or immerse ourselves in worlds devoted to the cultures we have chosen to belong to (I am writing this from a hotel room at Walt Disney World in Orlando).

As such, fandom, as in religion, is a source of purpose in life, enabling and empowering connection to culture and community, and is life-giving. Importantly, the culture of fandom is often predicated upon anticipation. We wait for the next movie trailer to drop, or the next episode to be released, and scrutinize it with frame-by-frame granularity. We wait in line for entry into the darkened caves of the theater to watch the next installment. And we wait outside the theme parks, rides, and conventions to experience heightened communal proximity with those who think and feel the same. And of course, such behavior is also frequently inter-generational. The baton is passed between father and son, ‘like my father before me’ as Luke Skywalker would have us believe.

I believe that fandom bridges both aspects of both the essentialist (belonging) and constructivist (doing) definitions of culture, and if we apply the lens of ritual, we can conclude that the active aspects of fandom can deepen one’s sense of connection and belonging. That one motives that other and accelerates one’s connection to community and culture itself. This has very much been my lived experience over the past 45 years of being a Star Wars fan, and I very much look forward to the next 45. In this respect, my connection to culture not only defines me, but it also makes me the most me I can possibly be.

Included below are two pictures of my home office, very much a shrine to the culture of fandom, and a strong manifestation of my individual connection to the cultures of music, sports and movie fandom.

Week 1: Piller Chapter 3

Piller articulates how hierarchical classification of difference became weaponized during the increasing colonialization of the nineteenth century. As imperial expansion increased, the overcoming of cultural difference became critical in asserting European superiority within a hierarchy written and determined by those of European origin. It placed those drawing those distinctions at the top. Propagated through poplar culture, it served as an anthropological tool to draw weaponized binary distinctions such them and us, black and white, evolved and primitive. In the twentieth century such hierarchies of superiority began to use the methods of inter-cultural communication to draw more positive understandings between cultures.

Week 2 Assignment 1: Reading Process Protocol

Where do I sit while I read?

In my basement home office on my couch in the early morning, with reduced lighting, minimal digital or physical distraction, a cup of coffee, and with a suitably sufficient window to ramp up over time into deeper, more focused reading (or in this case listening with the audiobook for around 4 hours from around 7am to 11am).

What do I do as I read?

I very rarely listen to audiobooks, so for this reading I sat calmly on the couch, hands crossed on my chest, eyes closed, periodically adjusting for comfort, stretching, laying down at times, but not focusing too intently on each word as it comes as with the exercise of study, but rather just letting the story come to me, more like listening to a play on the radio than having someone read something to me that I was seeking to retain for an assignment.

What do I notice as I am reading?

I grew up about an hour from where the story is set, so I am intensely familiar with the nostalgic, romanticized descriptions of the rural English countryside, its people, customs, culture, and norms. I recognize much of my own past in the detailed descriptions of small villages, decline in dairy farming, open fields populated with sparse hamlets, and fear of change, as they too are my own lived experience. Not as an outsider as with Naipaul looking in, but as someone who moved away and rarely returns. Within such a personal connection, I’m drawn to notice how my journey is the inverse of Naipaul’s ‘imperial chain which brings us together’. His is a journey of immigration from colony to England, mine one of emigrating to America.

What moves me in the text when I read?

I was moved by Naipaul’s beautiful use of compound adjectives in articulating the local connection to place from those who had been there for generations, and their contrast with the new, younger, agricultural workers. Unanchored, unpaved, unlooked at, unfenced, unpruned unnoticed and many more draw stark differences between the two sides of them and us, of efficacy versus tradition, of young and old attitudes to the land, and of the process by which the new migrants ‘turn the irregularities of the land into straight lines.’ In particular I was moved by the simple image of the new family leaving their front door open, and its use as a means for articulating changes in attitudes towards the house as a functional place of shelter, now stripped of its role as a home. My own lived experience was as one of these new migrant families when my military father was assigned to a nearby naval base, very similar to the firing range depicted in the text.

Which associations in the text excite me?

I was excited at the prospect of the story developing from one of anthropological observation to a murder mystery at the hands of a love triangle with the death of Brenda, murdered by Les, but with the culpability of Mrs. Philips in not passing along an all-important note, and the associations and parallels between the death of a migrant to the village, the cruelty towards livestock and the death of the local area more broadly. But this avenue is swiftly closed as the story returns to one of the descriptive declines of rural dairy farming.

When do I get bored reading?

There are several protracted descriptive sequences articulating Naipaul’s walks on the Salisbury plains, either in search of the perfect view of Stonehenge, or where he reminisces about lost histories as he goes about his walks in the countryside. These coincided with having listened for about 90 minutes. It was in these passages that my mind began to wander towards things I needed to do at work, chores around the house, what to cook for dinner tonight, going to the bathroom, and perhaps getting another cup of coffee. Because I’m so familiar with the actual locations of the story, I don’t have to think too deeply to be able to visualize where Naipaul is when he’s walking, and as such, the gap between listening and distraction grows smaller.

At which passages in the text do I lose my interest?

There are lengthy descriptive passages around the contrast between old and new house and barn construction, as well as discussions around the homogenization of the English seasons into one continuous, balanced, bland climate. It was in these protracted paragraphs that I began to tune out, only brought back in when the story returned to either personal perspectives, something I related to from my own lived experience, or moved the story along with human interest. It was challenging to just be in the story and let these descriptions wash over me, and I think I was too eager, perhaps even impatient, for things to move along.

What connections can I make to what I have learned about culture and language so far from everything in this module?

Brian Street’s anthropological approach to culture as a process, inclusive of essentialist and constructivist aspects of both being and doing appears strongly within Naipaul’s Jack’s Garden, with cultural changes motivated by the arrival of new farming technologies and the migrants (and problems) who arrive with them, the decline and eventual replacement of both people and place as the land gets worked and re-worked over time, the contrasting brevity of such cycles of life versus the broader arc of history, and how the economics, language (to ‘pick the pears in’), climate (relocating cows to the places of water during a drought), norms and behaviors within these cycles are never fixed in time and space.

Week 2: Piller Chapter 4

Piller describes linguistic relativity as the process through which the way we speak influences our perceptions of reality, nationality and identity, and our 'ability to engage with realities other than our own'. It was closely tied to European nation-building, weaponized during colonialism, and served to further position modes of difference and hierarchy which positioned white Europeans at the top of an anthropological system of cultural power and societal evolution. Piller draws upon examples of British colonization in Australia and the occupiers' failure to recognize linguistic relativity as a critical moral justification for expanded settlement and relocation of indigenous populations.

Week 3: Viewing and Response on Lecture with Anne Pomerantz

Professor Pomerantz's work on the role of humor positions it as a resource which is high risk, high reward, and a powerful binding force which can build rapport, resolve tension, and bridge cultures. Humor is often motivated by signaling shifts into more playful behavior through gestures or expressions, and intentionally directing the listener through pacing and sequencing to deliver a joke. But humor is like taste, varying between cultures, and carries risk, something I've found to be very dependent upon knowing your audience and 'reading the room'. I've found it can diffuse tension, but it can also create it if others don't appreciate the lack of seriousness, especially in high-stakes professional settings. There are often times I feel a joke 'brewing' in me, but the safer option is often to just suppress it, even though that's contrary to my authentic self. Pomerantz's work concludes that humor is more of an art than a science, and if you're uncomfortable with it, simply don't do it. Just be who you are!

Week 3: Piller Chapter 5

Piller's 'interested generalizations', like any stereotype, reinforce mono-dimensional reductions of identity, and present nation as a key overriding component for the basic articulation of cultural communication. But I think such distanced linguistic observations miss a powerful opportunity for providing more specific insight into how to overcome such generalizations, and perhaps even reinforce that which they seek to critique. But in our ever-polarized and partisan world such work of 'overcoming' is critical in removing prejudice and conflict. I think that if we acknowledge and spotlight stereotypes for what they are in our conversations, we can build the resources and capacity to also swiftly move beyond them in ways which support more nuanced, diverse and empathic perspectives. And through this work, we can become more inclusive of class, gender, ethnicity and other individualized traits, and ultimately towards a healthier climate of inter-cultural understanding.

Week 4: Reading Naipaul's Chapter "The Journey"

All journeys are seeded with echoes of previous arrivals and departures, welcomes and farewells, and for me this is true both in the reading and my lived experience as an immigrant. Naipaul nests several journeys inside each other. The journey of the protagonist from Trinidad to New York, and from Southampton to Oxford via London. There's also the journey of becoming for the author, from man to writer, the journey of colonial immigration, and the journey the reader takes with him as the book 'peoples an area'. But Naipaul describes how journeys are best understood in terms of returns, and how they shrink our world. That one has to leave to truly appreciate where one's from. This was unexpectedly true for me in Naipaul's observation that when we return to the place we came from, it can feel smaller as our own world gets bigger. This is very true of my experience returning to rural England having lived in New York. The place isn't different, but I am, and as I enrich my own experiences, and become different, those places 'left behind' in memory shrink, even though their reality is unchanged.

Week 5: Viewing and Response on Interview with LaDonna

If, as Ladonna Brave Bull Allard describes, culture is nothing more than morals and values to live by, then language is the binding agent which connects cultures, bridges difference, and connects us to the essential components of compassion. Through tradition and ritual, we learn to speak from the heart, and create the resources of compassion not just between ourselves, but also for the earth.

As an immigrant, even within the shared language of English, very often I've had to learn different languages from my own in this work, with new words, meanings and interpretations needing to transcend the spaces between people of differing cultural origin. These languages might be verbal, but also non-verbal, exclusive and gestural. I've had to learn new languages in the moment with immediacy, or through longer-term engagement, especially as professional relationships form and mature.

But I agree that if we speak from the heart, and lead with kindness and humility, people will listen. And if we speak with truth and respect, especially in moments of conflict, we can reduce spaces of difference, and truly understand one another.

Week 5: Reflection Piller Chapter 9

As Piller accurately points out, when we talk of culture, especially in the workplace, we are talking about inclusion and exclusion. We may pride ourselves on fostering inclusive cultures which seek equitable, diverse employees, but I think exclusion often goes beyond those who may dress or speak differently. In hiring, we often casually talk of culture fit. That an applicant will work well with those already employed. But when we use such language, we are defining boundaries. And with boundaries come inclusions and exclusions.

My experience has been that the best, most impactful hires are the ones which stretch the box, push at the boundaries, and make us all better through fresh perspectives and bringing things to the table no-one has thought of, and which transcend cultural background, not simply provide more of the same. Piller doesn't discuss unconscious bias beyond immigrant status for issues of faith, sexual orientation, political persuasion or gender identification, but these are all present when we make choices of fit, even if we're not vocalizing them. But I believe that the more someone can be their authentic selves at work, the more engaged and impactful they can be, creating a situation in which everyone wins.

Week 6: Reading Naipaul's Chapter "Ivy"

Naipaul's landlord is an enigma in passing. And in the glimpse he gets, he concludes so much. We see him as unexpectedly ordinary yet mysterious, benign above a veiled wave, and having the personality of a man expressed by his setting. A fat, round faced man who had withdrawn from the world, and we speculate on his artistic promise and lasting depression. He is the opposite of Naipaul socially and sexually, and even though an empire lies between them, they share a kinship in wanting to hide from the world.

I think Naipaul's glimpse is universal in the images we form of others, creating backstories and connections based on the simplest and briefest pieces of information. I've often created narratives for those I've just met, and swiftly drifted into unconscious bias based on the immediacy of my view of their appearance. I've made these assumptions based on language, clothing, ethnicity and social standing, and even though they are well-intentioned, carry enormous risk of prejudice when formed so swiftly. I've endowed others with qualities they simply don't have, projecting my own views onto them when they clearly don't exist, and like Naipaul, sought common ground in our fictitious, shared narratives.

Week 7: Viewing and Response on Interview with Jami Fisher

Identity is often formed in the limbic spaces between worlds. Between mother and father, internal and external, or in Dr. Fisher's case, the hearing and the deaf. Where these worlds intersect gives us the navigational opportunity to enrich our own understanding of the world, through what she calls a third culture. Sometimes these intersections create a voltage of creativity, other times the friction of conflict. But if we view ourselves as intermediaries between worlds, we can move to a place where we authentically hear others.

Importantly, identity formation in disability is frequently seen as deficit, benchmarked against an artificial view of normal. That we often define others through what they lack, rather than reframing how others visually orient themselves to the world. It's a form of reductive judgment which transcends disability and also applies to race, gender, language or lifestyle. Such reductions are rife with misunderstanding, doing more to divide us than bring us together.

I think being heard, both physically or emotionally, is critical to what it means to thrive in life. What we say, and what we hear, matters. But if we take the time to bridge the spaces between worlds, our lives can be made immeasurably richer.

Week 7: Reflection Piller Chapter 10

The language of digital fluency, and the harsh delta between those proficient and those not, can often motivate intercultural communicative tension. For those, like me, who self-identify as digitally native, embedded micro-context digital vocabulary is specific, acronym-laden, and often impenetrable to others. But it also determines my actions and proficiency in navigating an increasingly digital world. For those who view themselves as digital immigrants, it can as Piller argues, feel as if one's voice is being silenced. And if languages divergent from English have been marginalized historically, the macro-context of digital fluency and one's ability to adapt is swiftly replacing it. Misunderstandings are everywhere, reinforcing existing identity barriers of age and privilege.

I work closely with self-proclaimed 'non-technicals', with whom I often feel the need to translate or otherwise simplify what I'm trying to communicate, much like Piller's doctor struggling to rephrase questions with their patient. In efforts to reduce misunderstanding, on both sides, neither of us becomes capable of having anything other than a primitive exchange around needs and asks before the subject changes. They feel excluded and are fearful. I feel the need to simplify. Empathy is hard. Neither of us has the right words... yet.

Week 7: Reading Naipaul's Chapter ‘Rooks & The Ceremony of Farewell’

Naipaul describes a life's journey awakened by the idea of the end of things. Of vapor trails and disappearing chalk marks, and how our past conspires to conceal things from us. How all journeys are defined by arrivals and departures. That as time moves on, our years stack together, cycles running together in our memory, and how every generation takes us away from the sacred world of childhood.

For me, the experience has motivated a deeply introspective desire to write down the stories of my life for my daughter. To pass on to her all the journeys I've been on, all the welcomes and farewells, and for her to know how I came to be... me. Like Naipaul, the process is cathartic, and at times a means to write away the pain away of a premature farewell, or make sense of an enigma of arrival. But also to see myself, like Naipaul, as a sketch unfinished, with a storied past with many chapters left to come. Naipaul's journeys closely mirror my own, reaching out beyond the pages, taking my hand and saying 'I feel just like you'. I hope one day to do the very same for my daughter.

Week 8 Portfolio: Part 1 Nuanced Self-Reflection

Document 1: Week 5: Reflection Piller Chapter 9

As Piller accurately points out, when we talk of culture, especially in the workplace, we are talking about inclusion and exclusion. We may pride ourselves on fostering inclusive cultures which seek equitable, diverse employees, but I think exclusion often goes beyond those who may dress or speak differently. In hiring, we often casually talk of culture fit. That an applicant will work well with those already employed. But when we use such language, we are defining boundaries. And with boundaries come inclusions and exclusions.

My experience has been that the best, most impactful hires are the ones which stretch the box, push at the boundaries, and make us all better through fresh perspectives and bringing things to the table no-one has thought of, and which transcend cultural background, not simply provide more of the same. Piller doesn't discuss unconscious bias beyond immigrant status for issues of faith, sexual orientation, political persuasion, or gender identification, but these are all present when we make choices of fit, even if we're not vocalizing them. But I believe that the more someone can be their authentic selves at work, the more engaged and impactful they can be, creating a situation in which everyone wins.

Document 2: Personal Criteria for Reflection Selection

As a leader of people in a busy newsroom, my words have impact. Our journalistic mission is to help others make sense of the world, and that work starts with us. I am responsible for a modeled behavior critical to building great teams, but also for fostering the necessary time, space, and psychological safety for others to thrive in delivering upon that sense-making mission. In this work, what we say, and how we say it, matters. I never knew or felt how rewarding it would be to be able to build and grow a team beyond what you can give them. And how through measured language, coaching, and the inclusive behaviors of empathy, constructive listening, and authentic, equitable hiring, this work has been one of the most unexpected joys of my career.

Coupled tightly with this work is the idea of fit which I explore in my reflection. Who I think will thrive in joining our team, but who will also benefit others already here. And over time I’ve found that the most impactful use of language, the language that matters to others, is the one that’s the most… me. The authentic language of how I speak, how I dress, what’s important to me and what I choose to surround myself with. And being able to articulate all of this for someone else in crisp terms has not only been the work of the class so far, but also the joyful journey of my career. Now I’m in the position where I can foster it in others and reinforce it with the intercultural communication research we have been studying, making practical connections between theory and application even stronger both for me and for those around me at work.

Part 2 Term paper

Document 3: Embracing the Soil Which Grows the Best Version of Me

“The best moments in reading are when you come across something. A thought, a feeling, a way of looking at things, that you'd thought special, particular to you. And here it is, set down by someone else, a person you've never met, maybe even someone long dead. And it's as if a hand has come out and taken yours.” (Bennett, 2006)

Culture is a bridge between here and there. Between us and them. Between now and then. A sketch unfinished as much as a process of ritual and becoming (Naipaul, 1987). Of both belonging and doing as much as arrivals and departures (Street in Frei, 2023a). But often we find ourselves in the limbic space between language, of being neither here nor there. This is Naipaul’s lived experience as an immigrant in The Enigma of Arrival (Naipaul, 1987), but also mirrors my own. Of making a life in America but being from England. Forever being pulled by the nostalgia and language of where I’m from, but physically bound in space to the culture I’ve chosen.

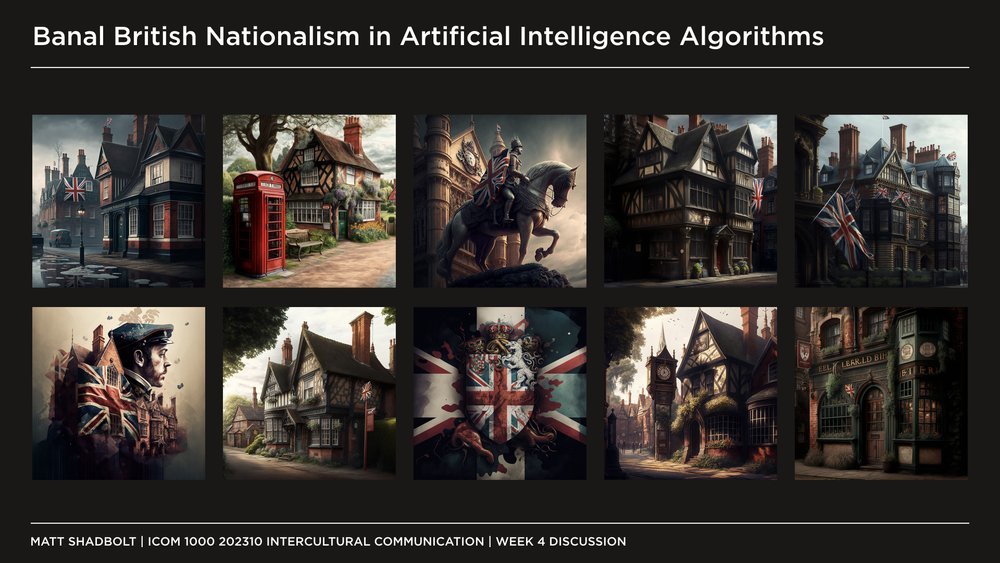

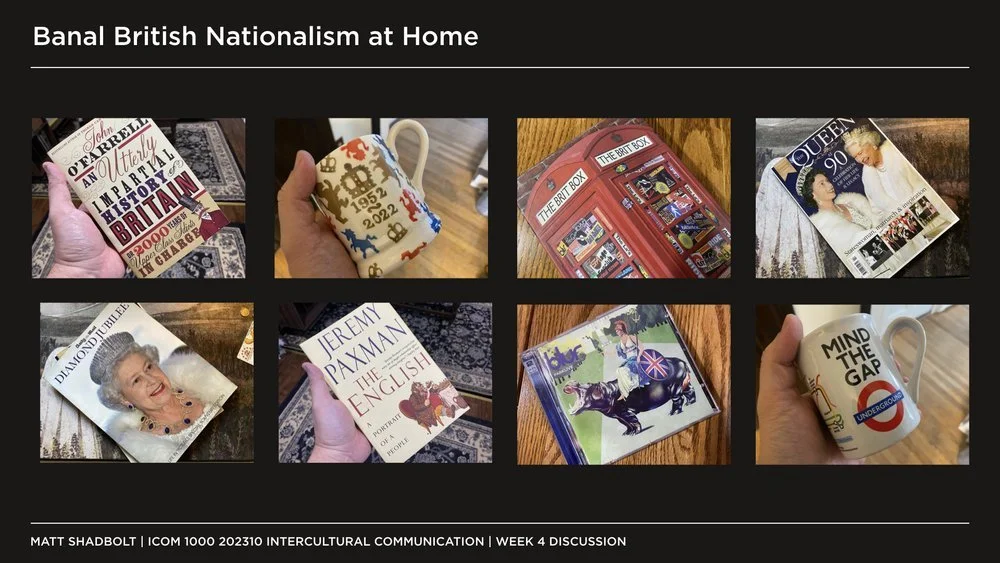

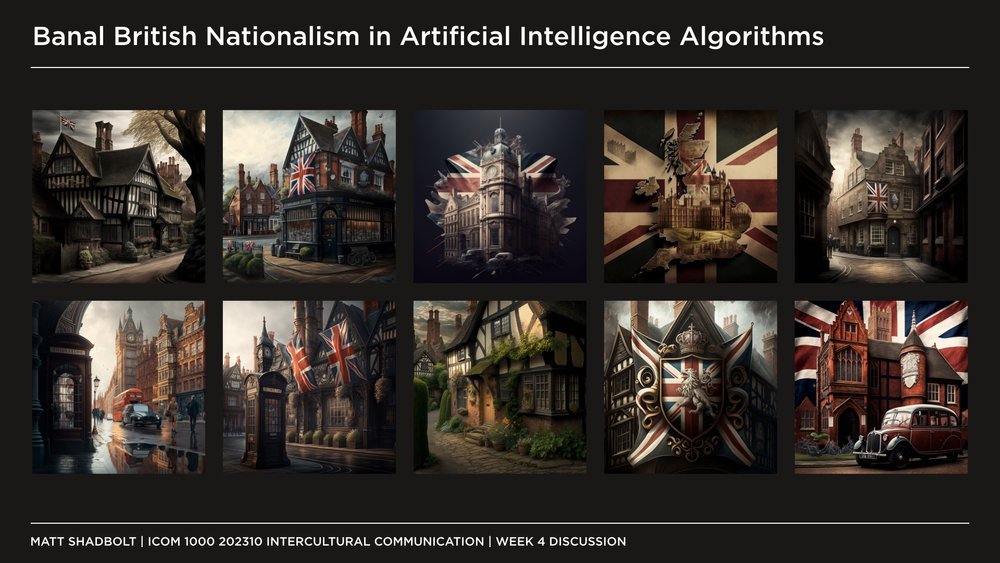

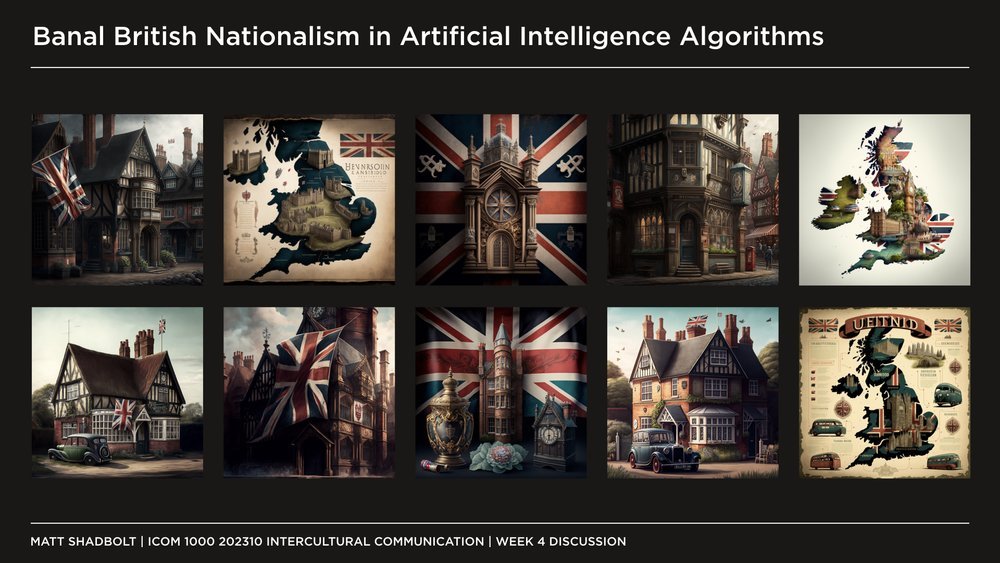

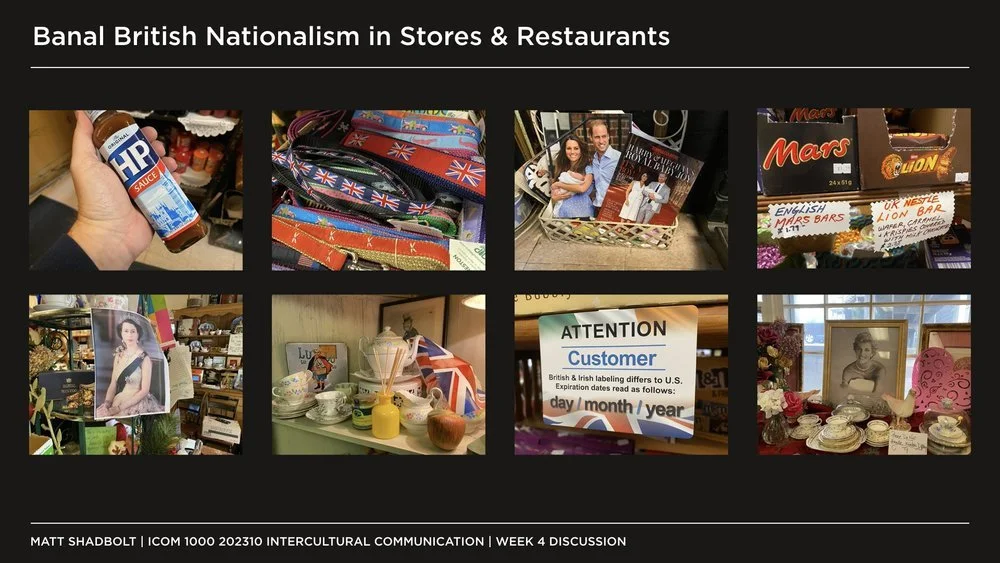

This limbic existence can feel nostalgic but is also one of displacement. Of never truly being local to anywhere. I’m at once both the kid who left England, but also the kid who’s not from here in America. I live a life surrounded by the signals of banal English nationalism (Piller, 2017), but the longer I’m in America, the less these symbols mean. In fostering the ability to engage with realities other than my own in forming an identity based on the blending of two nationalities, a hierarchy of preference forms (Piller, 2017). I dismiss the less desirable aspects of where I’m from but retain those deeper traits with which I align and share pride. Similarly, I can hold distant that which I’m uncomfortable with in my new home, while embracing that for which I moved here.

But this work carries risk, and the pitfalls of language are everywhere. Humor is often the crutch upon which I lean (Pomerantz, 2023), but it has also gotten me into trouble as my words often fall somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean, landing neither here nor there. But as Naipaul seeds in his nested journeys, echoes of previous arrivals and departures, welcomes and farewells (Naipaul, 1987), don’t just bridge, they strengthen the diversity and richness of one’s identity, and for me this is deeply true my lived experience as an immigrant. That the delta between here and there is something to be embraced as something which has made me uniquely… me. That I’m the binding agent between the cultures of my life. As an immigrant, even within the shared language of English, very often I've had to learn different languages from my own in this work, with new words, meanings and interpretations needing to transcend the spaces between people of differing cultural origin.

Boundaries between the spaces of here and there have had to become porous, and the depth of my experiences become richer when I embrace them both, rather than forcing a choice. But these boundaries are rarely fixed, and never final. That we are perpetually in states of arrival and departure, of welcomes and goodbyes, and of doing and becoming. That culture and language have no end points, and that even if we choose to delineate boundaries for ourselves, they are meant to be stretched in service of others.

Ritual has been a binding agent between language and culture the longer I’ve lived in America. Rituals of food, travel, work, family, and happiness have all brought me closer to those around me and solidified a stronger sense of home. America has adopted me, but I’ve also adopted it, and the perpetually fluid cycle of adoption, of bringing others into your life, as LaDonna Brave Bull Allard suggests, is the very essence of everything (Frei, 2023b).

Others may come and go through our lives, passing in moments like Naipaul’s landlord (Naipaul, 1987), but my experience of being neither here nor there, of America being my home but ‘over there’ being where I’m from, has formed in me, as Jami Fisher’s work explores, a ‘third culture’ (Frei, 2023c). A place where the voltage of creativity between worlds allows me to truly carve out a space to be the most me. The best version of me. The most authentic me. It’s a space where I must listen more intently, translating between worlds into a language which is uniquely mine.

Where I’m from isn’t the past. It’s fundamental to my present. And where I am in the future is shaped by not just the chapters of life already written, but by the chapters all around me. That culture and language aren’t bridges at all. They’re the soil in which our lives thrive. And as my roots continue in burrow deeper in my home country, they are richer and stronger for the nourishment I give them and the seeds from which they’ve grown.

Document 4: Critical Review

Shadbolt makes sense of the limbic spaces of his immigrant experience through binary and metaphor. By establishing introspective spectrums of here and there, of arrivals and farewells, and of past and present. Seeking to position his life’s journey somewhere on each axis to deepen his understanding of the things around him. These binaries create sense-making bridges between his experiences, but he dismisses the bridge metaphor in favor of one of roots and soil. Of how life’s journey isn’t about spanning culture and language, but more so a richly deep system of roots reaching back into the past to frame the present.

Shadbolt’s attempts to reconcile the idea of home as an immigrant, through its origin as an emigrant lean on experiences of ritual as a binding agent, but also the recognition that being neither here nor there is an aspect of life which is uniquely his. That the experiential blending of culture and language in his past has afforded him the opportunity to grow into the most authentic version of him he can be. A version where he can thrive irrespective of place. Transcend and stretch boundaries of language. And carve out a place for himself in the world in which his roots can grow with others.