PROW1000

Fundamentals Of Professional Writing

Week One

Reflection

I’ve shared three recent pieces of writing. Two personal, and one I wrote as a review for The Penn Moviegoer. The piece ‘When you fell asleep forever’ was written the day after I said goodbye to my cat of eighteen years. My heart was broken, and I wrote to process the pain. A cathartic dealing with loss. This sentiment is also reflected in the piece ‘Pierced through the heart but never killed’, which speaks of the ache for old friends long gone. That feeling of wanting to be remembered by others as much as you remember them. The third piece, a movie review of one of my favorite films, Leaving Las Vegas, also deals with loss, but more fondly and through a lens of nostalgia.

By day I work in the NBC Newsroom, surrounded by those telling the stories of the world in real-time. I write all day, but it’s the kind of writing that’s more about questions and answers, communicating status, and serving as the oil on which our teams run. I love to write, but I don’t consider what I write at work to be the kind of writing I would do by choice. I don’t ‘lose myself’ to the music of writing the way I do when I write for myself. And I rarely get to choose the topic on which I have to write. I’ve always enjoyed writing, am surrounded all day by writers, but have only in recent years begun to rekindle a love of writing for myself. Inspired to write down the stories of my life by my wife for our daughter, I’ve loved the process of giving her all the stories of my life to read one day, a process I wish my father had done for me. I’ve written about surviving cancer, emigrating to America, what it means to lose friends and pets, and even a lengthy dive into my lifelong Star Wars fandom. When I write these, I feel energized and inspired, something I hope my daughter will share when she’s older too.

In all my writing, I love to write about what I know, but also about what I believe. What I feel to be true, even if that wasn’t what I did in the moment. Even in the most academic of papers required for school, I always seek to make the thoughts crisp, the language enjoyable, and the argument interesting. I’ve learned that editing can be my best friend, and lengthy sentences my worst enemy.

My main strength as a writer is my ability to connect my personal experiences to a broader thematic truth. To find connection in what’s happened to me in service of something which might help others. That through such writing, a hand might come out of the page, take the reader’s, and say ‘I feel the same as you’. My greatest weakness is editing, although I feel as if I’m getting better through more constrained practice in writing for school. I also don’t feel as if I write as much as I’d like to. I write sporadically, rather than frequently, writing large amounts in concentrated bursts, rather than regular small amounts which connect into a larger whole.

I love to read and have always been a reader. I’m not a fast reader, but if the book captures my imagination, I can easily consume it in a matter of days. I mainly read historical non-fiction, with a particular passion for musical and film biography and tales of the British Empire. My major at Penn is ancient religious tradition, and I have loved spending time with some of the sweeping mythological epics from Greek, Roman, Hindu and Buddhist cultures.

I work in a busy newsroom, so deadlines are in my blood, and I can’t miss them. I don’t require help with organization, but I do often find the need to ‘sit’ with material and absorb it for a period before committing time to write. I might prepare some handwritten notes to organize my thoughts, but my best writing for class has usually been spent with a few days of thinking time ahead of actual writing and editing. It can feel like procrastination, but it isn’t. As such, I like to get ahead in class to give myself this time in advance.

Working in a newsroom also thrives on directness. There is no time for pleasantries when news is breaking. As such, I have a thick skin for criticism, and if you see something, I want you to say something. I would much prefer you to be direct and tell me exactly what you think. I know it will only make me better, which is why I’m here.

Week Two

Learning Outside My Comfort Zone

Over the past year, I have become fascinated by the specific kind of writing involved in working with generative artificial intelligence, specifically developing the procedural knowledge required in crafting what to tell a bot to do. Being able to produce a meaningful response from a platform like ChatGPT or MidJourney requires its own language, its own nuanced, cumulative iteration, and rests heavily on having a deep wealth of existing, declarative knowledge upon which to layer a prompt.

Being able to craft a great output relies heavily on technical skill but being able to share it with the world has been a step far outside of my comfort zone. Earlier this year I decided to begin sharing my work on Instagram, which compounded my declarative and procedural knowledge of prompt crafting with the conditional and affective knowledge domains of creating for an effective social presence. This process has been much more challenging.

The conditional knowledge required in when and where to speak, who to respond to and why, or even where to shut the conversation down, leans heavily into the idea of Kairos, an experience that I have largely experienced through trial and error. That in-built sense of knowing when to act, when to decide, and when to read the digital room to an extent that one knows what ‘the right time’ to take an opportunity means.

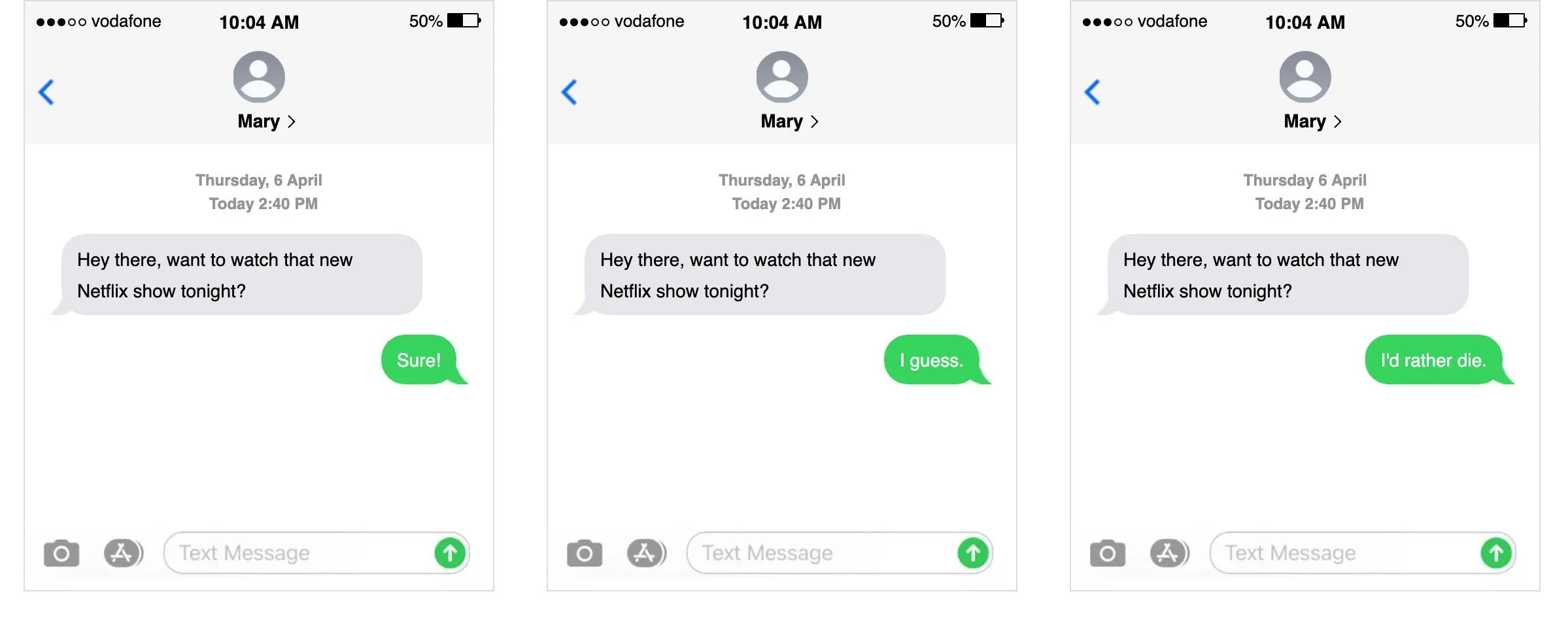

In this work I’ve needed to adjust my digital affective knowledge, which is different from my real-world affective knowledge. Attitudes and emotions are expressed differently online, and much is missed in intent. So far, I’ve found the most effective approach for me emotionally is to write minimally, lean on word and phrase blockers to filter out incendiary messages, and ultimately, to let the work speak for itself.

The work of adjusting my declarative and procedural knowledge in making work through its additive application in the real world through conditional and affective knowledge isn’t new for me as I do this all day at work but has often been uncomfortable in the context of work that’s more personal.

The Question of Expertise in Writing: Summary

Where does written expertise come from? What factors account for the delta between the academic writing students produce at college, and the professional writing graduate employees engage in at work? How might we approach the discussion from an ethnographic perspective, and what initial hypotheses might we draw? These are the questions posed by The University of Washington Tacoma’s Anne Beaufort in her opening chapter ‘The Question of Expertise in Writing’ at the beginning of her book ‘Writing in the Real World’ (Beaufort, 1999).

Observing the written learning behaviors of four women in a small, urban non-profit organization over the course of a year, Beaufort’s study examines how we might define written expertise, and draws out specific examples of what expert writing might entail. Importantly, Beaufort correlates the need to close the gap between college graduates’ inability to handle sensitive writing tasks with concerns surfaced by harmful, costly business risks such as legal action. Beaufort suggests that written expertise is a combination of both general and local knowledge, growing in specificity and contextual understanding over time, to the moment where those sufficiently skilled can intuit the most efficient and impactful ways to write.

But it’s an approach which goes beyond the procedural academic rules of grammar, punctuation, and composition, and is highly dependent upon context switching, especially in our modern, digital workplaces. Beaufort also introduces the idea of the discourse community, the already accepted practices between groups of people who are writing to each other, and for whom new employees can feel removed. What you know, and who you are to others, is just as important as to whom you’re writing, but scholars disagree on what constitutes expert writing, because of course all writing calls upon different cognitive and knowledge domains, which are often culturally elusive to both the writer and the reader.

However, Beaufort’s immersive ethnographic research following the four women seeks to examine not just the issue of learning to write in new social contexts over time, but the difficulties in crossing the boundary from academic to professional writing situations. Her expressed aim is to understand how these socialization processes work, and build them back into school programs, promoting more effective (and most importantly for business owners, cost efficient) preparation for workplace writing in recent college graduates.

References:

Beaufort, A. (1999). Writing in the Real World: Making the Transition from School to Work. [Digital file]. Retrieved from https://canvas.upenn.edu/courses/1705580/files/120452117/download?wrap=1.

Week Three

At the time of John Swales' writing, the idea of discourse communities was over thirty years old, and has been widely discussed by linguists as a framework for understanding how the conventions and expectations of language operate inside of groups. Swales initially situates his definition inside of three types of discourse community - local (groups who all work in the same place), focal (associations which span geography but align under a common cause) and 'folocal' (a hybrid of both).

However, as John Swales argues, over time it has become necessary to reconsider how these communities are differentiated by factors such as localization, specialization, allegiance and both internal and external pressures.

Initially defined by Swales, discourse communities have six characteristics:

A broadly agreed set of common public goals

Mechanisms of intercommunication among its members

Participatory mechanisms to provide information and feedback

Utilize and possess one or more genres in the communicative furtherance of its aims

Have acquired some specific lexis

Have a threshold level of members with a suitable degree of relevant content and discourse expertise (Swales, 2017)

Yet as Bazerman observes, "most definitions of discourse community get ragged around the edges rapidly" (Bazerman, 1994), and as the world has changed in the resulting thirty years, so has the concept of discourse community, motivating the need to reconsider the six original criteria. Swales updates the initial six definitions, and adds two more. These reconsidered definitions broaden the original scope of discourse communities to acknowledge their capacity to flourish in darker worlds, their virtual existence in digital communities, incorporate feedback loops, definitions of ownership, and expansion of community-specific language and hierarchy. To these, Swales adds 'silential relations', the sense of things that do not need to be said or spelt out in detail in words or writing, and 'horizons of expectation', in articulating defined rhythms of activity, a sense of history, and value systems for what is good and less good work. (Swales, 2017).

Wenger's 'communities of practice' intersects with Swales' work in that 'they are groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly' (Wenger, 2015). Engaged specifically with the process of collective learning, such as a group of engineers working on a shared problem, Wenger centers his definition across the dimensions of domain (an identity with a shared interest), community (groups which form relationship to help each other) and practice (people who develop a shared set of resources over time).

Communities of practice appear frequently inside of modern organizations as a conduit for enabling employees to take responsibility for their own improvement, to connect learning and performance, and to create connections across different job functions in service of solving business problems.

The discourse community I previously described in my work at NBC News is folocal in that it serves both internal and external challenges and pressures - the needs of the business, and also the needs of news readers looking to make sense of the world. But we do this through intersecting, matrixed communities of practice. The outcome of our internal communities of practice across the NBC newsroom, engineering, design, marketing and many others results in making sense of the world for the discourse communities we seek to serve. When we do this well, for example in the context of a breaking news story, our business grows, but so does the discourse community in attracting more people to what we do.

Internally, our community of practice is focused upon solving problems, improving the craft of our reporting, and furthering our goals around revenue and audience growth. Externally our discourse community seeks to make sense of the localized and focused world around them through many of the characteristics Swales presents. They have methods of intercommunication between their members, have channels of feedback, expressed goals, and their own specific, often impenetrable (in the case of CNBC) language. But these communities intersect in the context of the front-end news experience of a homepage, a news broadcast, or on the home screen of an app. It is where our work as a community of practice touches the discourse community we serve.

But as Swales strongly advocates, the nature of this intersection is often fragile, especially in the context of a product predicated upon built trust. It can be eroded in a tweet. The relationship between community of practice and the discourse community it serves necessarily evolves and adapts over time as news cycles come and go, new technology becomes available, and as the internal dynamics of groups change. But we've found that the best way to serve both the internal needs of the business and the evolving needs of news consumers is by fostering a strong community of learning, problem-solving, collective responsibility and most importantly, trust between people.

Discourse Community

Earlier this year my world at work got a lot bigger. I had previously led product efforts for CNBC, overseeing the brand’s digital presence across the web, mobile apps, and streaming platforms. In January my role expanded to do the same, but for all six NBC news brands: NBC News, MSNBC, CNBC, The Today Show, E! Entertainment, and Telemundo. The complexity and scale of my world increased by a factor of six, which is still both thrilling and daunting.

In making this transition, the familiar discourse community I’d known at CNBC for the past four years became one of six diverse and very different communities. For each brand there exists both the various internal discourse communities across job functions which we need to navigate to do the work, but there’s also the external discourse communities we service in our efforts to make sense of the world. The real-world MSNBC community is radically different in its consumption of the news, their motivation for sense-making, and their news gathering habits throughout the day from the E! community for example.

Yet in the context of the Swales’ characteristics of discourse communities, there does exists a commonality across all NBC news brands in a common public goal of helping millions of users make sense of the world every day. Each brand may differ in tone and tactics, but the principle of service is consistent through them all. Each brand has individual membership expertise, but also its own often impenetrable insider language. MSNBC teams often talk of ramen, fronts, packages and vitals, where The Today Show will talk of reskins, discovery, baskets and martech. My team, spanning all brands, is both specific and general, often having to translate between newsroom conversations, especially within written conversation.

Module 3 Reflection & Goal Setting: Discourse Communities

Last week I wrote that I’d become fascinated with the aspects and applications of conditional knowledge, and that I often find it challenging to navigate an appropriate sense of when and where to use one’s declarative and procedural knowledge.

Over the past week and reminded by a post-it note reminder on my screen of the word Kairos, I’ve sought out constructive opportunities to say less in both my written and verbal communication. A deliberate effort to step out of my comfort zone and use the resultant space to find more consistent time to lose myself to the music of writing for myself. But in stepping back, I’ve found that doing so isn’t just good for me, it’s good for others. It affords others in the room the opportunity to speak up, to problem solve, and to create spaces where they can learn from each other. In other words, my focus on the application and use of my own conditional knowledge is creating more space for others to build a stronger community of practice between themselves.

But I think it’s more than just allowing others to speak. It’s about fostering a more conscious environment of shared learning, which isn’t always about speaking or writing first, much as the compulsion to do so exists, especially as a leader. And this shared learning, this sense of the people in my team learning from each other in addition to learning from me, has clear benefits for all of us improving our communicative craft. To echo Swales, it’s a fragile balance though, and an approach which needs to flex up and down throughout the day based on audience and intent. Sometimes it’s better to jump in when we see folks drowning not waving. Sometimes we need to step back and let a situation unfold for itself, interjecting only where we can be helpful, and not to interject as a means unto itself.

My goal this week is the same as last week. To leverage sparser, but effective written communication at work to create the space to build a weekly habit where I self-publish one new piece of written work for myself. But my understanding of my goal is strengthened through its application into building a better community of practice. And when we do this, we don’t just generate momentum and excitement for ourselves, we generate it for our users, and everyone wins.

Week Four

Collaborative Joke Writing: Group 1

Our recipe: A three-part format following the rules of:

The situation / the context: Opening the stage & setting up

The response to the situation / something relatable: The angle on the stage and twisting the context

The punchline / reveal / the pull back: Changing and misdirecting the angle of the stage, delivering the joke

Our joke: My daughter has been learning to drive. It's been so stressful for everyone. Well, hopefully her golf game is improving.

Our revisions: Following our recipe, we felt that by reading the joke aloud it helped us to understand the cadence of the delivery, the brevity of the build-up and the importance of adding the 'well' at the punchline. 'Well' is also a means by which we can add a sense of self-deprecating resignation to our story. Both as a signal that the joke is about to be delivered, but also to make the joke's musical rhythm flow a little more harmoniously.

Our reflection: In reflecting upon the exercise, it was helpful for us to be able to deconstruct a number of existing jokes, and draw out similarities in framework and self-deprecating delivery, and the Rodney Dangerfield jokes were the most effective in being able to extract a consistent, replicable format. But in doing so, it was important to think about imitation as a place from which to then make the jokes our own, and crucially, to treat the joke as something to be delivered out loud to others rather than read. And when we do this, we experience the bliss Barthes describes in trying to make a social connection through our writing, in this case humor, but also create the music and rhythm of laughter between people.

Press Release

Target Publication: The New York Times / Media Section

PRESS RELEASE

EMBARGOED: 4/3/2023 9AM ET

NBC NIGHTLY NEWS INCREASES VIEWERSHIP, CLOSES GAP ON ABC

NBC’s Nightly News increased its viewership across the board in Q1 2023 vs. the prior quarter by over 300,000 total viewers. This improvement closes key demographic gaps vs. ABC against the prior quarter by 5%, making it the closest gap in the 25–54-year age demographic between the networks since 2020. In year over year performance, Nightly News cut the total viewership gap vs. ABC by 12%.

Nightly News now averages over 7.5 million viewers, 37% more than CBS, with 1.2 million viewers in the 25-54 age demographic, and beating CBS by 365,000, a 44% difference. In Q1 2023, Nightly News also saw its 3rd straight quarter of digital growth, with over 200 million total video views, reaching over 680,000 YouTube viewers.

During the week of March 20th, Nightly News was the 5th most-watched program in all of television, averaging 6.7 million total viewers, excluding specials and syndication, and marked its best week in digital since September 2022 with 1.8 hours viewed per user.

Cesar Conde, Chairman of NBC Universal News Group: “The increase in digital viewership of Nightly News reflects a successful renewed investment in our flagship news franchise, leveraging the insightful, determined and sense-making spirit of our newsroom during a critical moment. Our viewers are watching longer, but also consuming our journalism in more diverse places, particularly on mobile devices. We recognize that the news increasingly needs to meet them and make sense of the world around them wherever they are.”

As the organization plans for the 2024 election, it is also investing in real-time digital polling capabilities in partnership with its parent company, Comcast. NBC News also plans to continue its investment in new audiences in the coming months, with new distribution platforms such as TikTok and Peacock already seeing sustained growth, especially with younger news consumers.

“The hand of history is upon us” said Lester Holt, host of Nightly News, of NBC News’ digital opportunities ahead. “In an ever-polarized political climate, more and more viewers are turning to NBC News to help them make sense of the world, and our mission is that when they do, we are here to deliver the most exceptional journalism and storytelling experiences we can.”

NBC’s Nightly News airs live at 6.30pm ET weekdays on all local NBC stations, as well as digitally at NBCNews.com, on the NBC News iPhone and Android mobile apps, and on all streaming services. Previous and archived episodes can be found on the Peacock streaming service.

ENDS

For media enquires contact: Abby Marks, Vice President of Public Relations, NBC News Group, abby.marks@nbcuni.com, t: 862.219.1012

Notes to editors:

For more information about NBC Nightly News, visit https://www.nbcnews.com/nightly-news.

For more information about NBC News Group, visit https://www.nbcnews.com/.

For more information and a biography of Cesar Conde, visit https://www.nbcuniversal.com/leadership/cesar-conde

NBC News Digital is a collection of innovative and powerful news brands that deliver compelling, diverse and visually engaging stories on your platform of choice. NBC News Digital features world-class brands including NBCNews.com, MSNBC.com, TODAY.com, Nightly News, Meet the Press, Dateline, and the existing apps and digital extensions of these respective properties. We provide something for every news consumer with our comprehensive offerings that deliver the best in breaking news, segments from your favorite NBC News shows, live video coverage, original journalism, lifestyle features, commentary and local updates.

NBC News is part of the NBCUniversal News Group, a division of NBCUniversal, which is owned by Comcast Corporation. For more information about NBCUniversal, please visit NBCUniversal.com.

NBC News is pleased to offer closed captioning on long-form content and certain other content that it makes available on television and online via websites and apps on mobile devices. To report an issue or concern regarding closed captioning on NBC News programs viewed on television or online, please contact us at affiliate.operations@nbcuni.com or 1-866-787-6228.

Module 4 Reflection & Goal Setting: Genre

This week I’ve been thinking a lot about genre’s role in determining my purpose and motivation for writing. The exigence which flexes up and down throughout the day as writing, especially professional writing, shifts between difference audiences and discourse communities, different platforms and genres, and the adjustments I must make, often in the moment, in tailoring my writing to be impactful.

What I’ve realized this week is that so much of my written communication, especially in the more casual and informal channels such as Slack, is not impactful or purposeful at all. Many times, it is just writing for writing’s sake. Lost in the miasma of digital noise, and only contributing to the distraction of others. And while I still have the word Kairos taped to my monitor from a previous week, the learnings around genre supplement not just seeking out the right moment to speak or write but augment it with making that moment purposeful. By first asking the exigent question ‘what do I want to happen?’ I don’t just write, I write with purpose, and connect my writing to something more thoughtful, and with more pronounced, deliberate motivation.

So, while I’m building better muscles for knowing when to write, this goal this week is to pair that sentiment with the exigence of what I write. What do I want to happen here? What do I want the recipient to do? How might I make my writing more purposeful and deliberate, both for myself and the different communities I interact with throughout the day? How might that change based on the genre?

Week Five

Module 5 Reflection & Goal Setting: Rhetoric

This week I’ve been thinking a lot about how the tools of rhetoric wrap around my existing building blocks of Kairos, still taped to my monitor from a previous week, and the learnings around genre supplementing not just seeking out the right moment to speak or write but augmenting it with making that moment purposeful. Last week I asked myself the exigent question ‘what do I want to happen?’ to connect my writing to something more thoughtful, and with more deliberate motivation. Now that I’ve been focused on these aspects of my writing for four weeks, I’m forming habits and noticing more consistent behavior in how I write. I’m catching redundancies. I’m also catching where I’ve been blissful in my writing at the expense of clarity and understanding. So, while I’m building better muscles for knowing when to write, last week I paired that sentiment with the exigence of what I write’. This week it’s not just when I write, or what I write, but how I write. And making what I write count.

I’ve found the most critical tools for me are clarity of thought and brevity through editing. Shaving words off sentences, sometimes even letters off words, just to help bring that extra level of clarity to a thought in someone else’s head. This ruthless editing is forcing me to be clear in thought, but also clear in style. It untethers my writing from the lengthy descriptions which may be blissful for me to create, but far from blissful to consume.

I found a great clip of Jerry Seinfeld describing how he writes jokes, and how he’ll look for the connective tissue between thoughts, trying to get the phrases to fit together neatly like jigsaw puzzle pieces. I think a lot of this applies to my building blocks of Kairos, exigence, and rhetorical brevity. What’s new for me is the realization there is genuine bliss in being understood, and the tools of rhetoric, punctuation, purpose, and brevity are what I’m going to work on this week.

Module 6 Reflection & Goal Setting: Reasoning

Working in a newsroom carries the often-heavy weight of inductive reasoning. Both in making sense of the world for others, and for drawing conclusions and directions for ourselves based on what we know, and more often than we’d like, what we don’t. Our product teams listen intently to the needs of our users, attempting to shorten the space between that which we are inferring through inductive reasoning, and that which we have more confidence in through the harder math of deductive reasoning. Very often we fall somewhere in the limbic abductive space of neither, with our incomplete set of observations necessarily leaning on the information we have leading to hypotheses as to the most likely explanations based on our experience. Our abductive reasonings have become increasingly questioned in an era of fake news, and where data doesn’t always beat opinion.

Last week I wrote about the shift from the bliss of writing towards the bliss of being understood. That they’re not mutually exclusive, and that the most blissful experiences in writing are when both writing and reading are blissful. Tactically for me this is a renewed focus upon punctuation, purpose, and brevity in my writing, building upon the previous week’s bricks of Kairos, purpose, and the need to make what I do write, count.

A lot of the work I do requires explanation. Why we’re doing what we’re doing. Why we’re spending what we’re spending. Why we think our work is going to move a metric of interest. Importantly, this is critical work that I need to draw out of those in my team, so for this week’s goal I’m going to coach others in their own brevity and clarity, through making brief and clear written recommendations, and asking purposeful questions of them. It’s both an exercise in being able to improve the clarity and brevity in the writing of those around me, but also a bootcamp for me in practicing what I need to be doing myself in modeling the behavior for others. The specific genre of feedback is a common one for managers, and needs to be succinct, purposeful, and clear. The recipient needs to understand what’s actionable, why the feedback is happening, but also be able to positively receive it again in the future. So, this week I’m going to spread my goal socially to the rest of my team as a means of strengthening what I’m doing in my own writing, but also in theirs.

Week Six

Crisis Management

Task 1: Analysis & Synthesis

United Airlines’ series of responses to a situation where an overbooked flight resulted in the physical removal of a passenger is a wonderful illustration of the language contained in I.A. Richards’ belief that rhetoric is the study of misunderstandings and their remedies. During four corporate communications over four days, United and CEO Oscar Munoz struggle with increasingly desperate rhetoric for a solution which spreads beyond the organization’s control.

The first communication is primarily concerned with the facts as understood by an anonymous internal voice at United. It’s a cold set of brief statements, contains an impersonal corporate apology, and directs those wishing to follow up with ‘the authorities’ to diffuse the situation, but gives no means of doing so.

The second communication, distributed to social media and attributed to Munoz himself, attempts to walk back an increasingly volatile situation unresolved by the first communication. Again, this is all about United. He mentions that it is upsetting, explains what his team is doing, and continues to suppress the root cause of the problem, why the flight was overbooked. The physical removal of the passenger, as a measure of last resort in adherence with aviation guidelines, is not United’s fault, but it is their problem. The communication ends with the truth, that United is seeking to expedite a solution, covert language for making this go away.

The third communication is internal from Munoz to his team. Again, Munoz and United stand their ground. We read of the defiance of the passenger, the polite asks of the United staff, the adherence to the established procedures, and Munoz even commends his team for going above and beyond. However, internal communications such as these can rarely be relied upon to stay internal, and terms such as ‘involuntary denial of boarding’, ‘each time he refused’, ‘our agents were left no choice’ and ‘officers were unable to gain his co-operation’. Importantly, for the third time, it ignores the voice of the passenger, who has entered into a contract with the airline that with their purchased ticket, they expect to fly. A contract United has broken.

The fourth communication, issued as a press release and supported on Twitter, exaggerates, and continues to enrage. The responses of outrage, anger, and disappointment Munoz references, and the ‘truly horrific’ treatment of the passenger acknowledge neither the issue that the passenger was his passenger, nor what they are going to do about the culture of overbooking which caused the issue. He mentions that he’s going to ‘fix what’s broken’, but what’s broken here is the ownership of the problem, procedures which risk the removal of paying passengers, and a lack of empathy for those choosing to fly with United.

Task 2: Crisis Management Memo to United Airlines Executives

Sent: Monday April 17, 2023

To: United Executive Staff, United Communications, United Social Media, United Legal

From: Matt Shadbolt, Communications Director, United Airlines

Re: How we respond to urgent situations

Dear colleagues,

As Oscar often says, our strength is the ability to delight our passengers. When we do this, our business grows. Today we begin the rollout of several new communications initiatives to help us all navigate these more effectively during the most challenging situations. These circumstances may not be our fault, but they are our problem. In times of stress, it is critical that the voice of the customer is the loudest and most important in the room, and that we are all listening with both ears.

Comprehensive crisis management training will begin next week, but I wanted to give you an overview of what to expect in advance:

· Intensive, personalized training programs designed to aid us in empathetic responses which are customer-centered and use language which both protects United and addresses the root cause of the incident.

· A new web portal for us to share case studies, best practices, and hear from those at the gates who are on the front lines with our passengers every day. It is critical to our success that the voice of the customer reaches the boardroom.

· New social media guidelines, drafted in collaboration with our legal department, which are designed to help us respond in a timely fashion, but also acknowledge that ongoing communication and transparency is the key to owning the problem. If we don’t know, we need to say so. If we’re still waiting for someone to get back to us, we need to say so. If someone is upset, we need to say so.

· Updated measurement tools for evaluating our progress against our shared communications goals. It is essential that we don’t think of crisis management as a project resolved by training, but as an ongoing commitment to improving the lives of those who fly with us. We will all measure, reflect and adapt based on what we hear and learn.

Our communications, just like our gate agents, are most effective when they come from real people working together towards solving problems. This begins with acknowledging that the problem is happening. We might not have all the answers, but we know how to find them, and humanizing how we respond to crises puts us in the same seat as our customers. It is not their crisis nor our crisis, it is simply the crisis. Our new tools will help us empathize with the passenger, hear their frustrations, and empower us to get what we both want, traveling with delight.

The United Communications team and I are so excited about the opportunity these new guidelines will bring in improving the lives of our passengers and front-of-house employees, but never forget that customer communications are everyone’s responsibility. Not just Oscar’s, and not just mine. We are all on this plane together.

I very much look forward to working with you all in our sessions next week,

Matt

Reasoning: Abductive Reasoning

The scenario: My car’s tire gets blown out on the highway on the way home from work.

Deductive Reasoning:

Hypothesis: My tire hit a pothole and blew out.

My tire hit a pothole. Potholes damage cars. Therefore, a pothole damaged my car’s tire.

Inductive Reasoning:

It’s well documented that most potholes damage most cars, and we all know that potholes tend to damage older cars even more severely. My car is ten years old and while I never saw what it I hit as I sped along the highway, it must have been a pothole that took out my tire.

Abductive Reasoning:

I never saw what I must have hit with my car, but I heard the thud on the driver’s side and knew I’d blown my tire out. The most likely scenario is that I’d hit a pothole, something which had happened to me before and for which the road has a reputation.

Reasoning: Logical Fallacies

The logical fallacy of appealing to fear is increasingly prevalent in the partisan politics of populist rhetoric. A fear which is usually tempered by voting for an outcome which solves the source of the fear. We see this in the appeal to fear of being overrun by the statistics of immigration, of the economic outsourcing of jobs overseas, and most costly, the fear of wearing a mask during a pandemic, or not. The appeals to fear on both sides of the vaccination argument articulate empirically catastrophic outcomes. A loss of control with the spread of infection if you don’t vaccinate. A loss of inalienable rights if an authority forces you to do so.

Most recently we see these appeals to fear with the current Ukraine crisis. An appeal to fear that Russian aggression must be stopped at all costs, contrasted with internal Soviet fears about the continued expansion of NATO. Very often our understanding and sense-making through what we consume through the media can be severely lacking. The appeal to fear permits us to simplify, to demonize, and to establish strict binaries of good and bad, them and us, right and wrong. Evidence and reasoning in our understanding is often in short supply, and we side with the position we’re physically in.

We also see this in the recent political rhetoric of the 2020 American presidential campaign, culminating in the highly persuasive call to action from Trump on the Washington Mall that ‘if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore’. A logical fallacy that lit the fuse in a crowd which subsequently attacked the capitol building to disastrous human effect.

However, political appeals to fear are effective to those who choose to believe them, because they appeal to our lived experience, which should not be discounted. They speak of simple solutions to complex problems and are action-oriented in ways that government bureaucracy can often frustrate. They appeal to those in search of immediate action. There is a reason we use them. They work. Often to disastrous effect, but they are nonetheless highly effective in motivating action and response in the most primal of ways. Where they may lack evidence and data, they make up in emotion and connection. And when our goal is persuasion, appealing to emotion through fear can be a very powerful means of gaining votes.

Reasoning: Narrative Reasoning

On the morning of 22nd January 1879, Lord Chelmsford was restless. As Commander-In-Chief of the British army in South Africa, his forces had been tasked with the imperialist suppression, and ultimate destruction of the indigenous Zulu people. Camped for the night in the shadow of the Isandlwana mountain, his sentries began to receive reports of thousands of Zulus massing to the north. At the same time, Chelmsford also received intelligence that the main Zulu army was moving toward them from their capital in the east. Faced with conflicting information, but spoiling for a decisive victory, Chelmsford elected to take half his forces with him east, leaving the remaining half, some two thousand men, to guard the camp at Isandlwana. Colonel Pulleine, a career military administrator, would be left in charge.

As Chelmsford’s column moved away in haste, those remaining at Isandlwana went about the daily business of the camp. As the column disappeared over the hills to the east, almost twenty thousand Zulus appeared to the north, approaching the camp with great speed. With only minutes to prepare, the British camp hastily braced for an attack. Armed with modern rifles and facing the shields and spears of their native opponents, the British bullets were assumed to be more than sufficient to deal with any encounter. But without any fortification in place, and with the British soldiers deployed too far from the main camp, the odds of hand-to-hand fighting had been greatly leveled in the Zulus’ favor.

As the Zulus raced towards the camp, the British held a steady rate of fire. But their supply lines were overextended, and the ammunition flow was beginning to slow as the firing increased. Pulleine, increasingly desperate, sent several messages for help towards Chelmsford’s column, with no response. As the Zulus absorbed great numbers of casualties, they were still advancing towards the camp. Suddenly, the sky turned black with a partial solar eclipse. The British firing stopped. The ammunition was gone. As one, the Zulus rose, and encircled the camp, cutting off any line of retreat. As the firing lines folded in panic, the Zulus slaughtered the nearly two thousand men in the camp, the greatest British military defeat against a local force. Less than a dozen British soldiers survived, having fled early during the battle.

Chelmsford, upon hearing of the destruction of the camp, returned that evening in utter disbelief, remarking “but I left over 1,000 men to guard the camp”. With dismembered slaughter everywhere, the looted camp was one of utter despair. But the Zulus hadn’t finished. The sky to the west was red with fire, as the nearby hospital at Rorke’s Drift fought the remaining Zulus with only one hundred men. It would be a battle immortalized as a great defense after such a crushing defeat earlier in the day and served to deflect the blame back in England away from Chelmsford, who had made one of the costliest military decisions in modern history.

Analysis:

The story of the battle of Isandlwana is one of hubris, poor decision making, poor preparation, and the misinterpretation of conflicting information. There are three main moments in the battle. Chelmsford’s decision to split his forces and head east. Pulleine’s lack of preparation in entrenching the camp. And the decision to spread the firing lines too far away from the supply of ammunition. All three result in humbling lessons for the British, and a sharp correction of the misplaced imperialist arrogance which came with the over-confidence in their technology and culture.

But as Mattingly suggests, stories such as these allow us to deal in human agency. These aren’t just nameless, faceless armies trying to annihilate each other. These are real people, panicking and fleeing for their lives, or being shot down in their hundreds. Fathers and sons. The historical bullet points of the numbers involved, the terrain traversed, or the survivors don’t express the human cost of the encounter, nor do they afford us the opportunity to learn from the British mistakes. As Mattingly continues, these historical casualty figures ‘portray the complex experiences of suffering and healing in oddly agent-free language.’

The most dramatic moment of the battle, upon which the day turns, is an eerie natural phenomenon. The solar eclipse blackened the sky just as the firing stopped, signaling to both sides that the battle was lost for the British. There are several key protagonists in the battle, but in my story, I draw out two of them, representing two very different aspects of the British position. The warmongering Chelmsford, eager to prove himself with a decisive Zulu defeat, and Pulleine, a camp administrator who was seen as a safe bet to guard the back door. But their roles reverse, and Chelmsford is left with nothing to do, and Pulleine faced with twenty thousand Zulus.

The myth of the battle has been immortalized several times in film, with many creative selections and omissions made each time. It is often depicted as a British defeat rather than a Zulu victory. There is often license taken with the story of what happened to the ammunition supply. And there is often discussion as to what was going on in Chelmsford’s head the morning of the battle.

But real stories like the battle of Isandlwana act as parables for us. Lessons about the over-reach of our confidence. An arrogance where we can’t hear what’s being said in front of us. A way of understanding that history doesn’t always belong to those who write it. And perhaps most importantly, that these stories are about people. Their real fear. Their real bravery. And their very real loss.

Reasoning: Poetic Reasoning

Frost’s poem Fireflies in the Garden describes that moment where day turns to evening, the stars begin to appear in the night sky, and draws scaled comparisons between the ‘up there’ of the cosmos and the ‘down here’ of the earth. The night’s stars are big, our artificial, emulative fireflies here on earth small and transitory. Our earthly stars burn bright but fade.

I read the poem more as a comparison between the stars of the sky and the artificial ‘fireflies’ we surround ourselves with at night. The illuminations of streetlights, headlights, and the homes of others, something Frost would have increasingly been seeing in cities and towns when he wrote this in 1928. The fluorescent lights which ‘never equal stars in size’ but emulate their warmth and glow, which flicker to life at dusk and achieve ‘star-like starts’. But unlike real stars, last a fraction of time, are functional, and serve a timeboxed purpose. A transience which reminds us that our time here is brief in comparison with the eternal light of the distant stars. And how all bright beginnings, which may feel exciting, inevitably fade with time.

Module 6 Reflection & Goal Setting: Rhetoric & Reasoning

This week I’ve been thinking a lot about how the tools of rhetoric wrap around my existing building blocks of Kairos, still taped to my monitor from a previous week, and the learnings around genre supplementing not just seeking out the right moment to speak or write but augmenting it with making that moment purposeful. Last week I asked myself the exigent question ‘what do I want to happen?’ to connect my writing to something more thoughtful, and with more deliberate motivation. Now that I’ve been focused on these aspects of my writing for four weeks, I’m forming habits and noticing more consistent behavior in how I write. I’m catching redundancies. I’m also catching where I’ve been blissful in my writing at the expense of clarity and understanding. So, while I’m building better muscles for knowing when to write, last week I paired that sentiment with the exigence of what I write’. This week it’s not just when I write, or what I write, but how I write. And making what I write count.

I’ve found the most critical tools for me are clarity of thought and brevity through editing. Shaving words off sentences, sometimes even letters off words, just to help bring that extra level of clarity to a thought in someone else’s head. This ruthless editing is forcing me to be clear in thought, but also clear in style. It untethers my writing from the lengthy descriptions which may be blissful for me to create, but far from blissful to consume.

I found a great clip of Jerry Seinfeld describing how he writes jokes, and how he’ll look for the connective tissue between thoughts, trying to get the phrases to fit together neatly like jigsaw puzzle pieces. I think a lot of this applies to my building blocks of Kairos, exigence, and rhetorical brevity. What’s new for me is the realization there is genuine bliss in being understood, and the tools of rhetoric, punctuation, purpose, and brevity are what I’m going to work on this week.

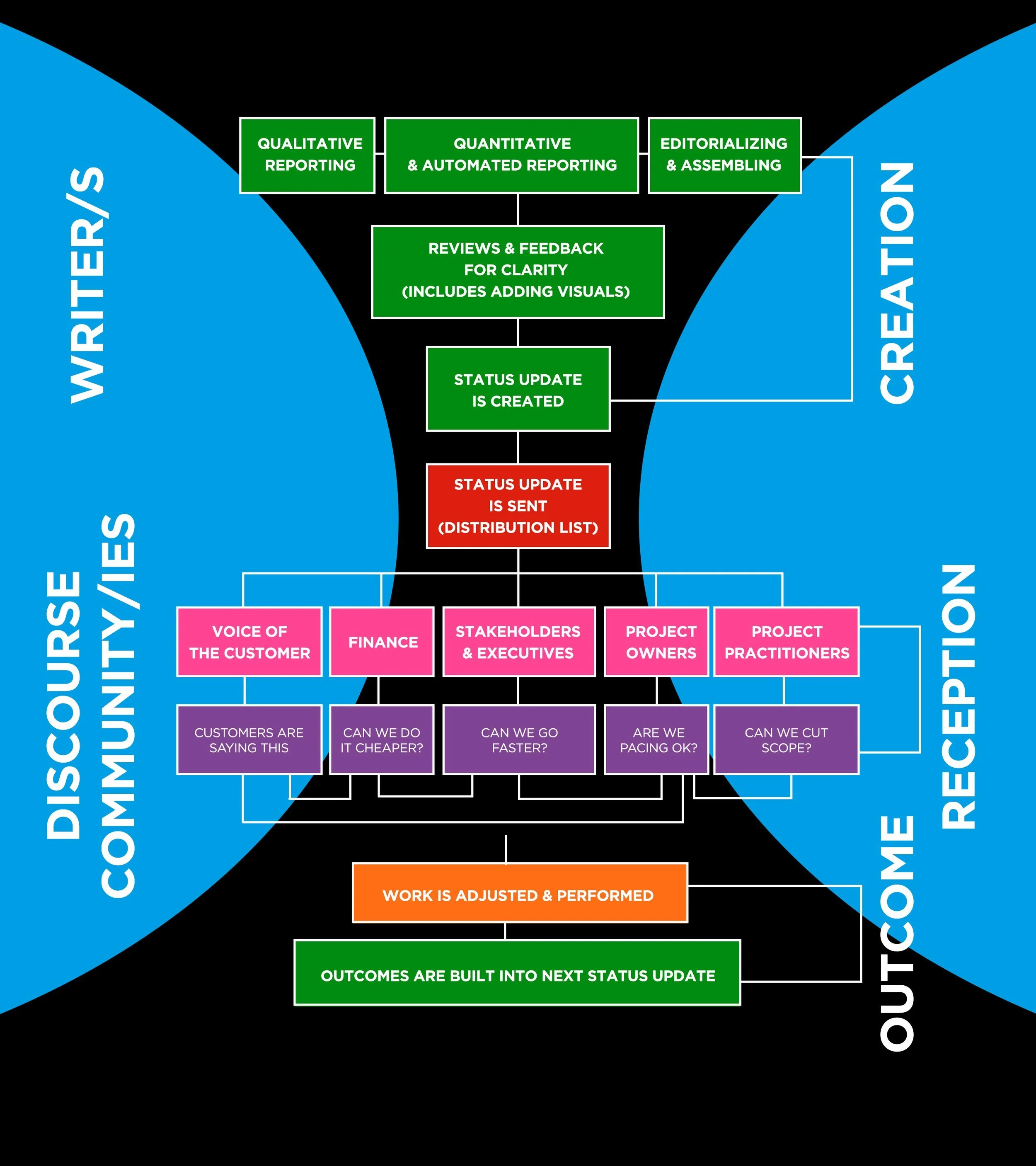

Activity System: The Status update

Status updates are often the oil upon which organizations run. They articulate what’s happening, what’s important, and who’s doing the work. They’re designed to provide visibility to those who care, those who are funding the work, and those who are invested in the work’s outcomes. They deliberately invite questions and are intended to motivate conversation in their recipients. Status updates as an activity system go through three distinct phases.

Creation, where the update is assembled, and written through quantitative, qualitative, and editorialized means. There are usually several authors involved as the sender of the update collates the information. When this phase is complete, the update is distributed to its intended audience.

Reception, where the intended discourse community asks questions of the update, seeks clarity on the finer points included, and asks for feedback from the other recipients of the update. They may also choose to bring in others so far not included. This is where most of the systemic activity of a status update happens, as the update does its work of driving discussions of pacing, efficiency, and when things are going to be completed. It’s also the phase where the work itself can change as the teams adjust the scope of the work in efforts to go faster for cheaper.

The final, and most important phase is the outcome. The status update must result in the work itself getting better, and these adjustments serve the purpose of beginning the cycle again for the next update.

Many status updates go unread by their intended audiences. They can be lengthy, dense, cumbersome in quantitative content, and often contain language not broadly understood by their recipients. But the most effective are those which make the work better, surface unforeseen items, and drive more positive outcomes.

Activity System: Mission Statements

NBC News Digital Mission Statement:

NBC News Digital is a collection of innovative and powerful news brands that deliver compelling, diverse, and visually engaging stories on your platform of choice. We provide something for every news consumer with our comprehensive offerings that deliver the best in breaking news, segments from your favorite NBC News shows, live video coverage, original journalism, lifestyle features, commentary, and local updates.

NBC News is driven by a responsibility to make sense of the world for the millions of people using our products every day. With this comes the need to make our storytelling deeply engaging, habit forming, and visually entertaining. Our mission comes to life when news is breaking, and sense-making journalism is critical. Such reporting spans many brands, voices, perspectives, and diverse opinions, but in that diversity comes a mission-oriented strength where we are greater than the sum of our parts. The mission is expressly created to be able to meet our users in the moment, whatever their brand, platform, or device of choice.

The persona here is one of authority, trust, and confidence. Someone you can turn to in wanting to understand the world. Someone you can rely upon to be in the room when the big things happen. But in that persona, there is a breadth of voices. That the diversity of personas, primarily organized by brand, offers a greater collective and cumulative means of sense-making.

With our Ukrainian coverage, CNBC may cover it from a stock price perspective. MSNBC may cover it from a political opinion perspective. And NBC News may be in Kyiv reporting live on what’s going to happen next.

Compelling, diverse, and engaging stories are the values which inform our journalism, but they also define our communication. We are intensely focused on the needs of our users, and our systems of communication prioritize listening and responding to their needs above all else. We write in user-centric language, and the genre of the customer testimonial is often an opinion-leveling format which frequently beats what we’re seeing in our data. Our quantitative work may lead us to conclude one thing, but the emotional sentiment of a user’s voice will often compel us to do something else.

Activity System: Outlining

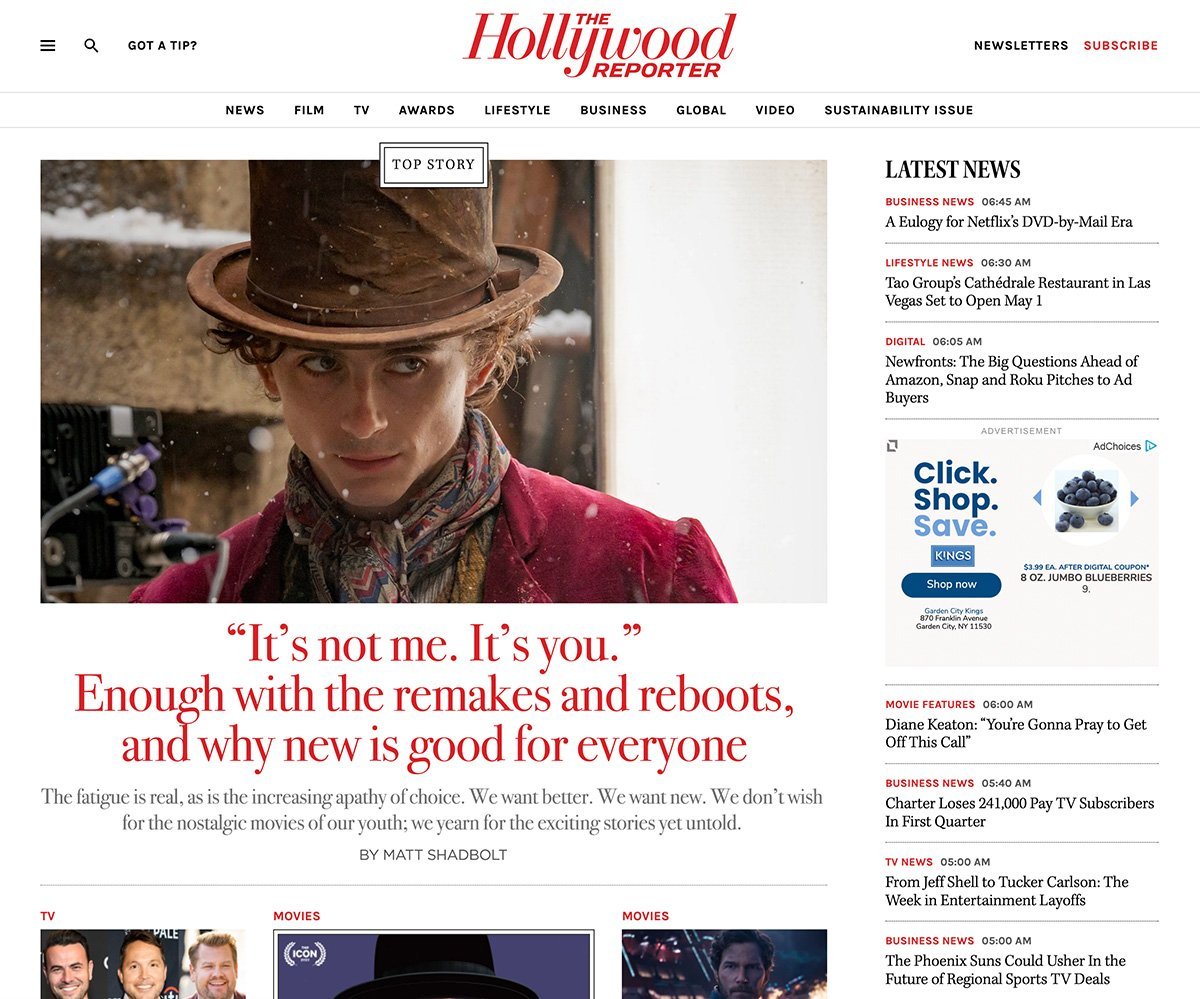

Justificatory Outline: Rhetorical Outline

Proposition: We should stop producing remakes and reboots of classic movies.

Audience: Film studio executives and investors, film producers, moviegoers, streaming platform executives, movie theater owners and franchisees, film and television union guilds, film critics and media executives covering the film industry

Premises: My readers care deeply about the art and craft of storytelling, but also the continued economic sustainability of the film industry. It is central to their professional future. They know that streaming technology in a post-pandemic world has caused fewer moviegoers to head to the theater but disagree on the tactics of what the future of success in original film making looks like in an increasingly uncertain media climate.

Genre: An opinion article published on a large liberal media website such as The Atlantic, The New Yorker, Variety or The Hollywood Reporter. This would enable the proposition to reach those with influence within the film industry, but also those passionate and invested in the future of cinematic storytelling.

Motive of Author: I feel that there are too many redundant, repeatable remakes being produced, at the expense of original storytelling and the surfacing of modern voices. Recent years have seen celebrated remakes of Planet of The Apes, Halloween, Top Gun, and Star Trek. In 2022 there were high-profile remakes of West Side Story, Scream, Pinocchio, and Matilda. 2023 will see remakes of The Little Mermaid, The Color Purple and Charlie and The Chocolate Factory. There are sixteen movie versions of Jane Eyre.

Motive of Reader: I believe that my target audience would be interested in the voice of a lifelong passionate moviegoer who is suffering from remake, reboot, and reimagining fatigue.

Goal: To insert the voice of the viewer into the economic discussion which motivates an industry culture of returning to existing intellectual property as a means of reducing financial risk. To help those invested in the future of film making hear the voice of the modern moviegoer and connect it to a path forward for supporting more original storytelling.

Rhetorical Strategies: I am going to need to lean on both the economics of risk reduction in contemporary film production but balance it with the need to surface the qualitative voice of an audience who yearns for new. I will need to balance the proposition that remakes are good for business, and that their continued production is successful, with the appetite for future-facing growth and originality. My voice should be passionate but not enraged, straightforward and empathetic, considerate of the challenges but thoughtful and delicate in the proposal of solutions to which I will not be as informed.

Logical Outline:

Premise 1: We all want to enjoy great movies.

Premise 2: The abundance of remakes and reboots has grown exponentially in recent years (supported by statistics)

Premise 3: The financial support for the production of original storytelling carries greater risk than existing intellectual property franchises

Proposition: New movies are better, and better for us, than remakes. We must carve out greater spaces of opportunity for original films to receive the same degree of audience reach, promotion and marketing as big-budget remakes and reboots.

Reason 1: Moviegoing is in decline, and accelerating in a post-pandemic, streaming-centric environment where competition for attention is being fueled by ownership of existing intellectual property, brand recognition, and increasingly smaller profitability. Focusing on new stories is a means by which to surpass the stability motivated by existing intellectual property, and offers a path towards economic growth.

Evidence 1: Statistical evidence of the sharp decline in domestic movie theater attendance in comparison to the rise of streamed viewership. Demonstrate that the rise in streamed viewership is not offsetting the declines from theaters, and that what’s successful in home streaming on platforms such as Disney+, Netflix or Peacock is primarily fueled by existing intellectual property (Star Wars, The Lord of the Rings, Halloween, respectively). Surface both quantitative and qualitative evidence of the lack of original programming at scale, but how several original releases have been incredibly successful at driving new and more diverse paid audience growth, deeper engagement, public recognition, and fostering community (The Mandalorian, Knives Out, The Power of the Dog, Roma, or The Irishman).

Reason 2: Original movies ignite our imaginations, inspire our children, and help us think differently about the world. They challenge us and help us learn about the world. They are a public good.

Evidence 2: Qualitative sentiment from passionate moviegoers about the current state of original movie production, supported by surveyed audiences. Demonstrate the positive benefits of original movies through vivid testimonials and the human stories of celebrities and popular individuals for whom going to the movies has been transformational.

Counterargument: Remakes and reboots have been incredibly successful in helping the film industry navigate the challenging, changing behaviors of viewers in an era where there is exponential choice, multiple platforms and places in which to watch, attention is commoditized, and where there is large appetite for more of the franchises viewers already love. They carry significantly lower financial risk than original storytelling.

Concession: It is true that remakes and reboots are very popular with the movie watching audience. I am not an industry insider, so I am ignorant to the internal economic complexities of the production business, but I am a passionate consumer of what they make. I am advocating for their paying audience.

Refutation: Doubling down on a culture of remakes and reboots is not a long-term strategy and is finite in application. Even the extension of existing intellectual property worlds such as the widening Marvel, Star Wars or Harry Potter universes is limited and already producing diminishing returns as those audiences fragment and the stories themselves weaken in comparison to their original treatments. There is growing sentiment and quantitative evidence that original productions are bringing in new and diverse paid audiences. So, while existing intellectual franchises serve a strong purpose for stabilizing and retaining the financial health of the industry, if it is to grow it must take the risk in turning to new, original, and more diverse stories to not just survive, but thrive.

Enough with the Remakes & Reboots

As far back as I can remember, I always loved the movies. But lately I’ve been feeling as if we’ve been growing apart. And it’s not me, it’s you. I want new things when you want old things. I want to travel to new places, experience new foods, and meet new people. You want to stay on the couch and watch what we used to watch when we were together twenty years ago. I want to go out with you and see the world. You want the world we already have. If things don’t change soon, I think we should break up.

All of us love a great story. It’s the glue that has bound us together for thousands of years. But in an era where streaming technology and the post-pandemic climate of diminishing theater attendance is causing the industry to tighten its belts, these stories have changed. Instead of heading to the theater on opening night we defer our excitement for when it hits our home platform of choice. We spoil the plots for ourselves by watching the granular vertical analysis on TikTok. And with infinitely expanding choice, we’re overwhelmed. Instead of surfing up and down the cable guide and finding nothing, we’re finding nothing in the horizontal carousels of Netflix, Prime and Disney Plus.

We’re tired because what there is to watch is what we already know. Remakes and reboots are everywhere. Hundreds of them. Do I watch the original West Side Story, or the contemporary re-imagining by Steven Spielberg? Do I watch the original animated Little Mermaid, or the culturally diverse live-action remake? Which one of the sixteen versions of Jane Eyre is the best? The fatigue is real, as is the increasing apathy of choice. There’s just too much, and more just isn’t more. We want better. We want new. We want compelling. We don’t wish for the nostalgic movies of our youth; we yearn for the exciting stories yet untold.

But we get it. Original movies are hard. And risky. And in an era where no-one goes to the movies any more, even making a movie at all is an achievement in itself. And of course, we know that remakes are popular. We know they gross billions of dollars, and that they’re good for business. But are they good for us? What is the term limit on the number of remakes of a single property? Production is more and more in the hands of a digital audience, but the abundance of remakes and reboots must fuel the need for more original storytelling, and there’s compelling evidence to suggest that original stories pull in increasingly newer, younger, and paying audiences. New stories such as The Mandalorian, which expand existing universes, or truly original scripts such as Knives Out or The Power of the Dog, are proving themselves successful for retaining streaming subscribers, but also growing the business. Remakes are good for the existing business, but if we are to get to a place of moving from surviving to thriving, we must focus on new.

These original movies ignite our imaginations in ways that remakes do not. They tell us something new about the world. About ourselves. And about what’s next. There are hundreds of wonderful stories still unmade. New stories remind us of the wonder of the medium itself. Of the awe we feel at seeing something new for the first time. When we first saw Darth Vader emerge from the smoke. When we first saw Buzz and Woody talk to each other. When we first believed that Superman could fly. Where is the wonder in the tenth Fast and Furious movie? Or the legitimate terror of the fourteenth Halloween reboot?

We’re willing to pay. We want to pay. But doubling down on a culture of remakes and reboots just isn’t sustainable. Not just for you, but also for us. Even the extension of existing intellectual property worlds such as the widening Marvel, Star Wars or Harry Potter universes is limited and already producing diminishing returns as those audiences fragment and the stories themselves weaken in comparison to their original treatments. So, while we understand that existing intellectual franchises serve a strong purpose for stabilizing and retaining the financial health of the industry, if it is to grow we believe it must take the risk in turning to new, original, and more diverse stories to not just survive, but thrive.

Module 7 Reflection & Goal Setting: Writing Process

This week I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the delta between the planning approaches motivated by activity systems and outlining approaches, and my own methods of writing. The main difference is that I have often relied upon the process of writing, even the bliss of writing, as the means of arriving at a proposition. And then used the process of editing to go back over what I’d written before in getting the premises to line up with the overall rhetorical argument. Indeed, arriving at a strong proposition while writing, is a blissful moment unto itself. That the act of writing was how I arrived at the proposition and was the motivating means of transferring a set of thoughts from brain to page.

That’s not to say that I never plan. Of course, I do. But very often the rhetorical work emerges from the exercise of writing, rather than the writing emerging from the outline. That the proposition becomes stronger through writing itself. This is also true in my professional communication, where the proposition frequently arrives somewhere in the middle of a thought, and rarely at the start. I feel as if I hear this a lot in writing advice. The idea of just keep writing. I don’t do it quite that way as I often find it hard to begin, needing to sit with something for a while before beginning, at which point it usually rapidly pours out of me. For me it’s healthier to think of this as a bi-lateral activity system, where the ecosystem of outline, act of writing, and spaces of rhetorical development co-exist within the same ecosystem, rather than as a series of distinct sequential moments.

But a powerful insight for me is to accept this, and to use the outlining tool to get to the point I’m making. Not instead of, but in addition to the bliss of writing. That outlining can serve as a kind of shorthand for hammering out ideas, and more importantly, the order in which those ideas should best appear for someone else. And how inside that ordering comes a systemic approach. That the order in which the argument is structured is part of a larger activity system of comprehension which starts with the outlined shorthand, grows in substance, and gets organized and re-organized in structure for clarity, and then ultimately leaves me to spend time with someone else.

This approach is going to prove invaluable for handling large amounts of information in future academic work, but it also affords me the clarity to take a pass at an outline that’s declarative, or another that’s procedural, and look for those spaces of opportunity to include not just want I know, or what I’ve found, but what I think. A space in which my own ideas or opinions are deliberately and systematically included, rather than being summarized in the closing paragraphs of a conclusion.

Last week I wrote of ‘a renewed focus upon punctuation, purpose, and brevity in my writing, building upon the previous week’s bricks of Kairos, purpose, and the need to make what I do write, count.’ Going forward as I reflect more broadly on the toolbox from the past few weeks, it’s all these things, but wrapped in the rhetorical, systematic work of making one’s writing matter. To go beyond the mattering bliss of my own joy of writing, and to make my writing make sense and matter to others, which feels like one of the best goals any writer could ever have.

Week Eight

Reflection Letter & Literacy Mapping

Dear Reader,

In my role as Head of Product for NBC News, I write all day. In my undergraduate studies, I write all night. But in much of my professional writing, I don’t so much write, as type. News is a deeply reactive business, and much of what I type is in response to something else happening. My work spans dozens of different genres which need to flex and adapt throughout the day, and my communications need to connect with diverse discourse communities both inside and outside of the organization. My work reaches hundreds of people inside of NBC, and millions of people outside.

In my academic work, the climate is intimate. Writing is still in response to a prompt, but the audience is smaller, the pieces more strictly evaluated. At school the stakes are more personal. It is more important to me that the work I do for school reflects a deep curiosity about the world and builds more thoughtful writing muscles. If my professional work is building a better understanding of the world for others, my academic work is centered around building a better me. It supports a journey of building the best me I can possibly be. Any grading involved at work typically shows up through the genre of feedback, but the stakes are different. At work my writing has time and cost implications, and there is enormous responsibility to be able to create an experience where millions of others are able to make sense of the world around them. The stakes are public, and highly visible.

Over the course of the class, I’ve steadily built a stronger foundation which began with drawing more deliberate attention to the when and why of my writing. The Kairos of what I write and the need to make what I do write, count. And in doing so, carve out those spaces of opportunity for those wonderful moments of Barthesian bliss. But not just the bliss of writing, the bliss which comes from being understood. Assembling a well-comprehended set of instructions or crafting a joke which lands well. I’ve had to focus on my clarity and made strides in confidence with being able to write less but mean more. I love to tell jokes, but they are always other people’s jokes. Something I’ve heard elsewhere that I’m repeating for others but claiming ownership over. I have a new appreciation for the craft of writing something amusing from nothing, and as an exercise in the rigorous brevity I originally sought it was a wonderful experience.

But like any journey of adventure, the path has not been a straight line of continuous improvement. While I’ve found moments of bliss in the rhetorical reflections and narrative reasoning exercises, I’ve found justificatory and reasoned argument more challenging. When I write to justify, I often write with passion and position. I fall foul of the desire to persuade and convince rather than reason. And that fire can sometimes run away with itself as the motivation to argue and over-supplement a case with reason and examples outweighs a more balanced and impactful set of propositions and counterarguments. This has surfaced a clear opportunity for me in setting a goal of being able to spot when I’m doing this, and to recognize how and when to make these arguments drive more successful outcomes. It’s not a desire to lessen my passion for a position, but more how clear reasoning might make such a position crisper and stronger. This is an invaluable insight for someone looking to drive consensus and momentum inside of a large media organization.

So, while I’m well used to the genre of feedback and evaluation, the genre of feedback about my writing is something new. The past few weeks have given me the language of genre, rhetoric, reasoning, knowledge domains and activity systems to be able to situate my writing more accurately as it stretches and flexes throughout the day based on professional, academic, or personal need. But it is a new language. One in which I am not fluent but will be with practice and effort. I began by thinking about a need for brevity, but as I end the class, I find that brevity is really a tactic inside of clarity. Clarity of argument, clarity of understanding in the recipient, and clarity of intent.

Along the way there have been distinct moments of bliss in writing. My analysis of United Airlines’ public relations crisis paralleled a real-life nine-hour delay in trying to fly home from Miami. I wrote the assignment as the real-life frustration was happening all around me and as I was able to observe what the gate staff were going through with their increasingly irate customers. It was a wonderful opportunity to turn a real-life situational frustration into an insight unique and timely to the assignment. I could see and feel what the airline wasn’t doing. I have included the assignment below.

Similarly from week six, I wrote about one of my favorite stories, The Battle of Isandlwana, where an entire column of British soldiers was wiped out by the Zulu army in one of the worst defeats in the Empire’s history. This was a story for which I already had deep declarative knowledge, and the exercise of recounting what happened was one of bliss. But being able to interpret the events, make sense of them, and apply affective and procedural approaches to what we might learn from such an episode was something I had only ever read about from others, not written for myself. As with the United Airlines case study, I was able to draw attention to the importance of human agency, and how, as I wrote, ‘as Mattingly suggests, stories such as these allow us to deal in human agency. These aren’t just nameless, faceless armies trying to annihilate each other. These are real people, panicking and fleeing for their lives, or being shot down in their hundreds.’ I have also included this work below.

Meeting the needs of those looking to make sense of the events around them is what we do at NBC News. It’s our place in the world. But the need for sense-making isn’t just for those who use our products. It’s critical for everyone engaging with my written work. Sometimes I will know the recipient, and target my words to them specifically, but often I don’t. When I write academically, it’s usually for an audience of one, or a small group of peers. When I write for work, the words leave me, and I relinquish control of them. Sometimes they come back to haunt me. However, through the lens of human agency, we allow ourselves to be wrong. That what we write can be fallible. That there is grace we can afford ourselves with what we write. That it’s what we write next that matters. And how we often have the opportunity to amend our words in retrospect as we learn. Looking for those opportunities is also something I’m actively building into how and when I write, but also fostering it in those around me. By modeling a behavior I’ve gained in this class, I am improving the communication of others too. This work is as communal as it is individual.

Armed with a new toolbox of insights and the means of identifying, naming, and adjusting to different knowledge domains, genres, and opportunities for clarity, I’m going to drive at three goals. First, recognizing when the bliss of writing is happening at the expense of brevity and clarity. And realizing that there is deep bliss in being understood as much as there is in losing oneself to the joyous music of writing itself. Second, using the tools of logical reasoning and justificatory writing, work towards not just the Kairos of when to write, or the exigence of what I write, but how I write. How I choose to craft a proposition and support it with a concise set of reasoning. How to construct a clear set of answers to the implicit questions I’m raising and ensuring that I’m not clouding my words with bifurcation. And third, using outlining to sharpen my thoughts as an act of writing unto itself. To not think of outlining as a distinct, separated preparatory part of the process, but to think of it as writing. That outlining is the first draft, not the paragraphs which it later drives. And how outlining can be a powerful tool towards editing, clarity, and brevity. Outlines by necessity should not be long, and they must get to the point swiftly. In this, they must be brief.

In conclusion, the class has changed me exponentially for the better as a writer. It has afforded me the opportunity to think about the craft and language of not just what I’m writing, but how I’m writing. Not just the declarative or procedural knowledge of what I do, but the conditional and affective aspects of how I do it. And most blissful, it has given me the time and space to sharpen how I tell stories which make sense in the heads of others.

Two examples of writing from the class:

Week 6: Crisis Management

Task 1: Analysis & Synthesis

United Airlines’ series of responses to a situation where an overbooked flight resulted in the physical removal of a passenger is a wonderful illustration of the language contained in I.A. Richards’ belief that rhetoric is the study of misunderstandings and their remedies. During four corporate communications over four days, United and CEO Oscar Munoz struggle with increasingly desperate rhetoric for a solution which spreads beyond the organization’s control.

The first communication is primarily concerned with the facts as understood by an anonymous internal voice at United. It’s a cold set of brief statements, contains an impersonal corporate apology, and directs those wishing to follow up with ‘the authorities’ to diffuse the situation, but gives no means of doing so.

The second communication, distributed to social media and attributed to Munoz himself, attempts to walk back an increasingly volatile situation unresolved by the first communication. Again, this is all about United. He mentions that it is upsetting, explains what his team is doing, and continues to suppress the root cause of the problem, why the flight was overbooked. The physical removal of the passenger, as a measure of last resort in adherence with aviation guidelines, is not United’s fault, but it is their problem. The communication ends with the truth, that United is seeking to expedite a solution, covert language for making this go away.

The third communication is internal from Munoz to his team. Again, Munoz and United stand their ground. We read of the defiance of the passenger, the polite asks of the United staff, the adherence to the established procedures, and Munoz even commends his team for going above and beyond. However, internal communications such as these can rarely be relied upon to stay internal, and terms such as ‘involuntary denial of boarding’, ‘each time he refused’, ‘our agents were left no choice’ and ‘officers were unable to gain his co-operation’. Importantly, for the third time, it ignores the voice of the passenger, who has entered into a contract with the airline that with their purchased ticket, they expect to fly. A contract United has broken.

The fourth communication, issued as a press release and supported on Twitter, exaggerates, and continues to enrage. The responses of outrage, anger, and disappointment Munoz references, and the ‘truly horrific’ treatment of the passenger acknowledge neither the issue that the passenger was his passenger, nor what they are going to do about the culture of overbooking which caused the issue. He mentions that he’s going to ‘fix what’s broken’, but what’s broken here is the ownership of the problem, procedures which risk the removal of paying passengers, and a lack of empathy for those choosing to fly with United.

Task 2: Crisis Management Memo to United Airlines Executives

Sent: Monday April 17, 2023

To: United Executive Staff, United Communications, United Social Media, United Legal

From: Matt Shadbolt, Communications Director, United Airlines

Re: How we respond to urgent situations

Dear colleagues,